Poonam Sharma

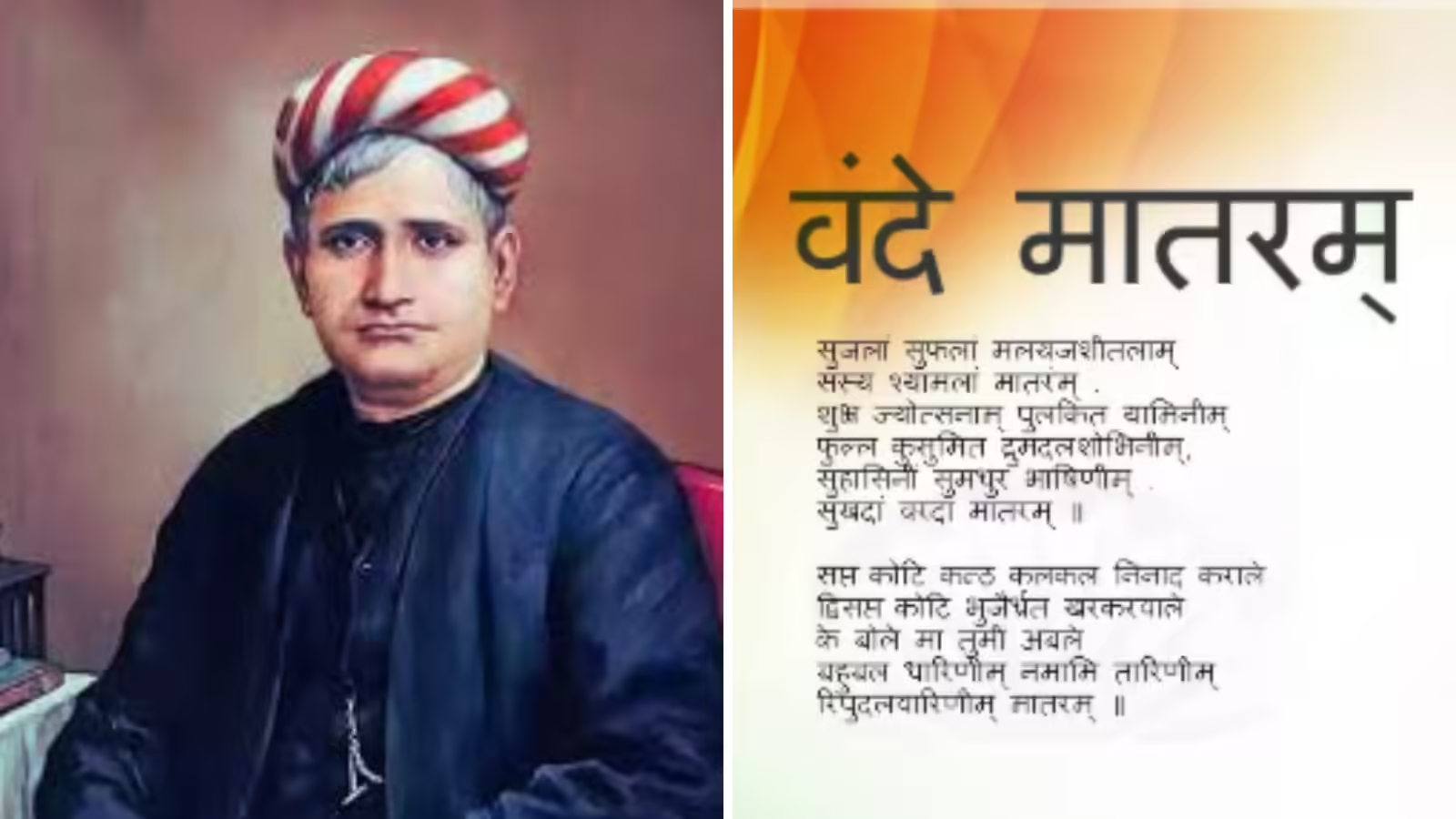

One hundred and fifty years ago, amidst the quietude of Bengal, a pen ignited a revolution that would eventually shape the destiny of a nation. It was Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s pen, and the flame he lit was called Vande Mataram. It was much more than a song; rather, it was a spiritual invocation, a literary masterpiece, and a political manifesto-one which gave India its first collective heartbeat of nationalism.

The Birth of a Song and the Birth of a Nation

Vande Mataram, written in 1875 and published two years later in Anandamath, was not poetry but prophecy. The day Bankim took his pen to paper and put down those immortal words-“Mother, I bow to thee”-he turned the abstract geography called Bharat Mata into a breathing mother, worthy of devotion, protection, and sacrifice.

The poem reminded Indians, during the time when British colonial rule had reduced them to political subjugation and psychological slavery, that their land was sacred, their culture divine, and their spirit unconquerable. It gave emotional articulation to an emerging idea—that India was not a colony, but a civilization.

The Anthem of Freedom

From Bengal to Punjab, from Maharashtra to Tamil Nadu, Vande Mataram became the battle cry of India’s freedom struggle. It inspired countless revolutionaries, poets, and patriots.

When Rabindranath Tagore first sang it at the 1896 session of the Indian National Congress, the whole assembly rose, with wet eyes and clenched fists pressed against the heart. Later, Sri Aurobindo called it “the mantra of national awakening.”

Vande Mataram echoed through the streets during the Swadeshi Movement in 1905, when Bengal resisted Lord Curzon’s partitioning, and with every echo, it was not a slogan but an act of rebellion. The seditious song wove its way into processions, pamphlets, and whispers of revolutionaries at the gallows. British officers, fearful of its power, forbade public recitations, but no chains could hold that spirit.

It kept burning as a lamp of hope in prison cells, on battlefields, in exile. It was the soundtrack of the nation’s rebirth.

Beyond Politics: The Spiritual Core

Unlike most revolutionary songs that fade with political change, Vande Mataram endures because it transcends politics. It is a song of dharma, not of ideology. It invokes not hatred for others but reverence for the motherland.

Bankim Chandra, whose mind was greatly influenced by the Bhagavad Gita, saw no conflict between devotion and duty. His Bharat Mata was not a goddess demanding ritual worship; she was the embodiment of nature, culture, and moral order. In his vision, serving the nation was the highest form of spirituality.

Thus, Vande Mataram became a bridge between religion and reason, between patriotism and prayer. It redefined love for the land as an act of moral and ecological responsibility.

The Modern Relevance: From Nationalism to Environment

While India celebrates 150 years of Vande Mataram, its meaning has expanded. The “Mother” we salute today is not only the nation’s cultural essence but also her rivers, forests, and soil. It is the same Mother who suffered at the hands of a foreign rule and now faces exploitation in the forms of pollution, deforestation, and climate change.

While the struggle for freedom wanted political independence, today’s era wants environmental independence, that is, freedom from the destruction we bring on our land.

Saying Vande Mataram today means pledging to protect the Ganga, the Himalayas, and the forests of the Deccan. It is to realize that without ecological consciousness, nationalism is incomplete.

Just as Bankim’s generation fought to free the motherland, this generation must seek to heal her. And in that spirit of Vande Mataram, the evolution will be from revolutionary nationalism to sustainable patriotism.

Cultural Revival and Global Resonance

Artists, musicians, and filmmakers alike still draw inspiration from Vande Mataram-even 150 years later. From Lata Mangeshkar’s soul-stirring rendition to the marching rhythms by the Indian Army, the melody remains timeless in its energy.

Every time the song plays to mark Independence Day or at any school function, it rekindles unity across languages, regions, and faiths.

Internationally too, Vande Mataram represents a civilizational statement: India’s nationalism is not imperial, but inclusive, cultural, and compassionate. It speaks of reverence for nature, respect for diversity, and the pursuit of harmony-values the modern world urgently needs.

Bankim’s Enduring Vision

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay was not merely a novelist or poet; he was a visionary to foresee India’s future role as a moral superpower. Through Vande Mataram, he reminded the Indians that freedom must rest on self-respect, not revenge, on character, not chaos. In the 21st century, when India is emerging as the voice of the world, Vande Mataram acts like a moral guide to remind us that power without purity and progress without sustainability are victories that ring hollow. To bow before the Mother today is to pledge truth in governance, ethics in economy, and compassion in technology.

Conclusion:

The Eternal Bow A century and a half has gone by since the whispered accents of Vande Mataram escaped the lips of a Bengali sage. Yet, its echo resonates in every Indian heart. It has outlived empires, ideologies, and centuries. It is the song of sunrise over the Himalayas, the rustle of banyan leaves, the rhythm of monsoon drums, and the heartbeat of a billion souls. While we celebrate 150 years of Vande Mataram, we are not celebrating just a song but reaffirming a civilization’s conscience. When we say “Mother, I bow to thee,” we do not salute history alone-we are invoking the future.