Preamble Politics and the 42nd Amendment: Revisiting a Constitutional Crossroad 50 Years After Emergency

Paromita Das

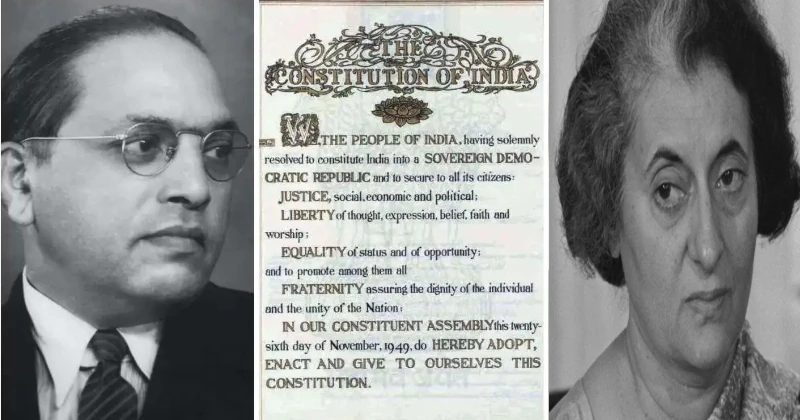

New Delhi, 28th June: On June 25, 2025, as Bharat solemnly marked the 50th anniversary of the Emergency—a time of political darkness and suspended freedoms—a long-standing debate resurfaced with renewed intensity. At the center of this reflection lies not just a memory of authoritarianism but a clause in the very document that defines Bharat: the Constitution. Specifically, attention has turned again to two words that continue to divide jurists, politicians, and citizens alike—“Secular” and “Socialist”—added to the Preamble through the 42nd Constitutional Amendment.

This is no dry constitutional squabble. At stake is the very question of what Bharat is—and what it is not. Were these words rightful reflections of Bharat’s evolution, or were they forcibly inserted into the democratic blueprint by a regime clinging to power through emergency decrees? The question continues to echo through the chambers of Parliament, courtrooms, and drawing rooms across the country.

Emergency and the Birth of a Controversial Amendment

It was 1976. The Emergency had strangled Bharat’s democratic soul. Parliament functioned as a rubber stamp. Civil liberties lay in tatters. Political opponents rotted in jails. In this climate of fear and repression, Indira Gandhi’s government introduced the 42nd Amendment—sweeping in scope and ominous in intent.

Among its many provisions, the Preamble was altered to include the terms “Socialist” and “Secular,” making Bharat a “Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic.” This transformation of the Preamble was executed without public debate, without parliamentary consensus, and without consultation with the people—the very people in whose name the Constitution was enacted.

While defenders argue the move aligned the Constitution with the country’s evolving identity, critics remain adamant: it was an ideological hijacking under the shadow of authoritarianism.

The Original Vision: A Constitution for All, Not Just the Ideologically Aligned

When Bharat’s Constitution was crafted under the guidance of B.R. Ambedkar, every word in the Preamble was debated, contested, and carefully chosen. Proposals to insert “Secular” and “Socialist” were indeed made—by figures like H.V. Kamath and Hasrat Mohani—but were decisively rejected.

The framers did not consider these values unimportant. Rather, they viewed them as already embedded within the broader promises of justice, liberty, and equality. The Constitution, after all, guaranteed freedom of religion and outlawed discrimination—hallmarks of a secular polity. As for socialism, it was seen as a possible policy direction, not a compulsory ideological framework for all future governments.

In other words, the original Preamble sought to be inclusive and flexible, not prescriptive or doctrinaire.

How Political Giants Saw the Amendment

It wasn’t just constitutional scholars who balked at the amendment. Political titans like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani openly criticized the way “Secular” and “Socialist” were slipped into the text. To them, the inclusion was not about reaffirming values—it was about entrenching a particular political narrative during a moment of national vulnerability.

During the Janata Party government that followed the Emergency, the 44th Amendment was introduced to undo many of the draconian changes brought in by the 42nd. It restored press freedom, reinstated judicial review, and imposed curbs on the executive’s power. Yet, ironically, the words “Socialist” and “Secular” were left untouched, perhaps due to the need for political compromise or the fear of reviving divisive debates.

Words That Define or Divide?

To understand the lingering discomfort with these words, one must go beyond their dictionary meanings. In practice, “Secular” has often been weaponized in Bharat’s political lexicon—used to brand opponents as either champions of pluralism or betrayers of cultural identity. Likewise, “Socialist” has vacillated between being a banner for welfare-oriented governance and a cloak for state control and inefficiency.

Critics of their inclusion argue that these terms have become political tools rather than constitutional principles. When a word’s interpretation is left to the whims of parties in power, it risks becoming a dog whistle rather than a doctrine.

A Missed Opportunity at the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court was recently called upon to reflect on this issue. In 2023, it dismissed petitions challenging the 42nd Amendment’s insertion of these terms. The court held that the words did not violate any constitutional provisions and had, over time, become part of Bharat’s democratic ethos.

While legally sound, this judgment sidestepped the more profound moral question: should a constitutional amendment passed during an era of suspended democracy still carry the force of legitimacy today?

A Constitution Must Reflect Consensus, Not Coercion

It is one thing to evolve as a democracy—it is quite another to rewrite foundational texts in the absence of public scrutiny. The insertion of “Socialist” and “Secular” into the Preamble was not merely symbolic; it was indicative of how easily a democracy can be reshaped when its institutions are weakened.

Supporters of these words argue they enhance Bharat’s commitment to justice and unity. But that commitment must emerge from consensus and reaffirmation—not imposition. As Bharat looks forward to its centenary as a republic, perhaps it is time to revisit whether our Constitution still reflects the will of “We, the People”—or whether it carries the imprint of regimes past.

Democracy Must Be Guarded, Not Garnished

The Constitution of Bharat is not a manifesto—it is a mirror of the people’s aspirations. The Preamble, as its soul, should reflect what unites, not what divides. Half a century after the Emergency, the scars remain. And with them, the persistent question: Should Bharat’s foundational document bear the legacy of a time when democracy was throttled?

It is not merely a matter of legal rectitude, but of democratic morality. If we truly believe in the ideals of liberty, justice, and dignity, we must be willing to interrogate even those aspects of our legacy that have survived judicial scrutiny but not the test of history.