National boundaries, often taken for granted as natural demarcations of political space, are in reality historical constructs rather than inherent divisions of the earth. If borders were natural or divinely ordained, rivers would flow within the confines of a single nation, deserts would lie strictly within one state, and mountains would belong exclusively to a particular polity. Yet, in practice, rivers like the Danube cross ten countries, the Sahara stretches across eleven, and the Himalayas span multiple states and nations. This alone discloses that boundaries are not carved by nature but by human actions, negotiations, and conflicts.

From the drawing of the Radcliffe Line in 1947, which brutally cut across communities, villages, and even homes, leaving millions displaced, to the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, which sliced Africa into artificial colonies without heed to its cultural and ethnic mosaic, boundaries have largely been outcomes of colonialism, treaties, wars, and political bargains rather than organic developments. India, as a post‑colonial state, embodies perhaps the most vivid example of this legacy, with the Partition producing catastrophic migrations and long‑lasting traumas.

Equally significant is the fact that passports-now considered indispensable-were not required until the twentieth century. The modern passport regime emerged only after the First World War, when surveillance, suspicion, and the tightening of sovereign territorial claims converged. In earlier times, mobility across regions was relatively fluid, subject more to dynastic authority than to modern bureaucratic nation‑states.

The Concept of Boundary

The theoretical underpinnings of national boundaries further reinforce their constructed nature. Benedict Anderson’s seminal notion of Imagined Communities posits that nations exist because their members imagine themselves to be part of a community through shared symbols, narratives, and institutions, despite never meeting the majority of their compatriots. The boundary, therefore, is not a geographic inevitability but a socially produced frame of belonging.

Similarly, John Agnew’s concept of the Territorial Trap critiques the assumption that states are fixed, natural containers of political life. Instead, he argues that borders are fluid, mutable, and reflective of power relations-constantly redrawn to serve expansionist or strategic needs. This is evident in the United States’ interventions abroad or China’s unyielding expansionist policies, which challenge the fiction of rigidly permanent territorial lines.

Refugees: The Insider–Outsider Question

Boundaries acquire their starkest human meaning in the plight of refugees, who by definition live outside the legal protections of their homeland. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defines a refugee as someone forced to flee their country due to a “well‑founded fear of persecution” for reasons of race, religion, nationality, social group, or political opinion.³ Intriguingly, refugees find no mention in the UN Charter itself but were belatedly recognized in the 1951 Geneva Convention, later expanded by the 1967 Protocol, which removed the original Eurocentric limits.

The present scale is staggering: according to UNHCR’s 2024 Global Trends Report, 123.2 million people worldwide have been forcibly displaced. This includes ~42.7 million refugees, ~73.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), ~8.4 million asylum seekers, and ~4.4 million stateless individuals.⁴ The numbers suggest that one in every 67 humans on Earth lives outside the security of a stable home.

The refugee issue exposes the tension between humanitarian duty and national sovereignty. On one hand, no country can remain indifferent to mass suffering; on the other, large‑scale refugee influxes often alter local demographies, creating anxieties and conflicts among native populations.

The Indian Experience

India presents a double paradox: though historically a haven for displaced populations, it has no formal refugee law and is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or the 1967 Protocol. Refugees in India are legally treated as foreigners, governed by laws like the Foreigners Act of 1946 and the Passport (Entry into India) Act of 1920. Yet, India’s judiciary, especially the Supreme Court, has interpreted Article 21 of the Constitution-the right to life and personal liberty-to extend basic dignity and protection to refugees.

The Partition of 1947 remains India’s most searing refugee crisis, with nearly 15 million people displaced across hastily drawn lines, accompanied by staggering communal violence and loss of life. Later, in 1959, the Chinese invasion of Tibet triggered another wave, bringing around 80,000 Tibetan refugees into India-a population that today numbers over 120,000. Both instances reveal how borders, while drawn in ink, bleed in flesh and memory.

The North‑Eastern region offers another lesson: the influx of refugees, particularly in Assam, has created demographic anxieties, ethnic tensions, and violent movements over fears of cultural and political marginalization. These tensions highlight how boundaries are not just lines on maps but also lived realities that shape identity, belonging, and conflict.

Conclusion: Boundaries as Fragile Fictions

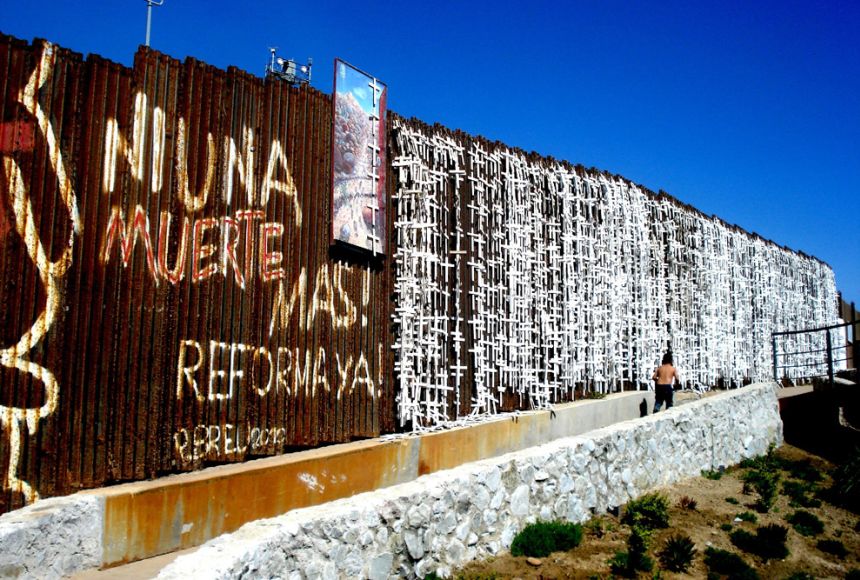

National boundaries, then, are neither natural nor timeless. They are human inventions-imagined, negotiated, and enforced through power, law, and sometimes violence. While they provide frameworks for governance and identity, they also produce displacement, exclusion, and conflict. Refugees stand as the most poignant testimony to the illusory solidity of borders: individuals uprooted because the lines of human imagination and political expediency fail to accommodate their right to exist in peace.

The challenge, therefore, lies not in erasing boundaries altogether-an impossible utopianism-but in rethinking their human purpose: ensuring they do not become cages of exclusion but rather frameworks of cooperation, dignity, and shared humanity.

Shivani Singh is student of Political Science, History and a prolific writer on Political issues .