Imperial Ambition and a Calculated Exile

Mir Jumla’s invasion of Assam in 1662–63 stands as one of the most dramatic yet paradoxical episodes in Mughal imperial history. Launched under Emperor Aurangzeb, the campaign combined territorial ambition with a subtle political calculation aimed at removing Mir Jumla himself, whose extraordinary power and independence had begun to unsettle the imperial court. Contemporary European observers, including a Dutch sailor attached to the Mughal fleet, believed that Aurangzeb deliberately sent the formidable general to a distant, hostile frontier in the hope that Assam would succeed where court intrigue could not. Mir Jumla, aware of the risks, nonetheless accepted the command, drawn by the promise of military glory and imperial favour.

Rapid Advance and the Shock to the Ahom Court

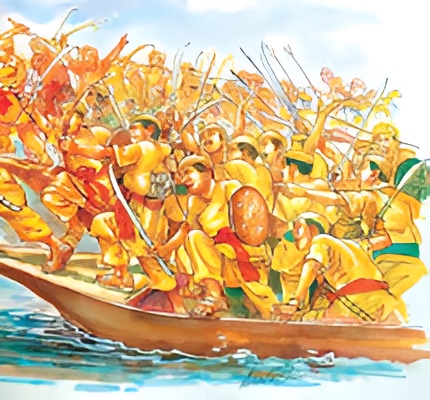

The invasion began in early February 1662. After securing Koch Bihar, Mir Jumla advanced swiftly into Kamrup, capturing Guwahati and Pandu by mid-February. By the end of the month, Mughal forces had pushed deep into Ahom territory. This rapid advance, supported by a strong riverine fleet manned partly by European sailors and gunners, stunned the Ahom court. Yet Assamese resistance was immediate. Ahom forces adopted guerrilla tactics—ambushes along narrow river channels, sudden night attacks, and systematic disruption of Mughal supply lines—turning the terrain itself into a weapon.

Terror, Retaliation, and Psychological Warfare

The violence of the campaign soon reached appalling levels. According to the Dutch eyewitness, Mughal troops inflicted extreme punishments on Assamese captives: beheadings, impalements, floggings, and the public display of severed heads hung from trees. Some prisoners were forced to carry the heads of executed comrades before being killed themselves. These acts were intended to terrorise the population into submission. The Assamese responded with equally grim reprisals. Captured Mughal soldiers were tortured, and after death their bodies were fastened upright on boats and sent drifting down the Brahmaputra toward the Mughal fleet—an eerie form of psychological warfare that deeply unsettled the invaders.

The Illusion of Triumph at the Ahom Capital

Despite fierce resistance, Mir Jumla reached the Ahom capital in August 1662. On 17–18 August (12–13 Muharram 1073 AH). Coins were struck in Aurangzeb’s name, and imperial authority was ceremonially proclaimed. In Mughal chronicles, this moment appeared as a triumphant climax. In reality, the Mughal army was already on the brink of collapse.

Monsoon, Disease, and the Disintegration of the Army

Relentless monsoon rains flooded camps and poisoned water sources, triggering epidemics of fever and dysentery. More than half of the contingents were wiped out by disease and surprise Assamese attacks. Food shortages became desperate. Of 173 paddy heaps seized, only sixteen could be preserved. Prices soared, and soldiers were reduced to eating coarse red rice without salt and eventually the flesh of horses, camels, and even elephants. Guerrilla attacks continued through September and October, while famine and pestilence ravaged the camps. Officers openly declared they would rather desert than endure another rainy season in Assam.

Illness, Mutiny Fears, and the Turn Toward Negotiation

Mir Jumla himself fell gravely ill in December 1662 while advancing toward Namrup, reaching Tipam on 18 December—the farthest point of his campaign. Facing the real danger of mutiny and annihilation, he reopened peace negotiations. Jayadhvaj Singha, recognising the temporary vulnerability of the invaders yet unable to expel them outright, sought to secure their withdrawal. These negotiations culminated in the Treaty of Ghilajharighat on 22 January 1663.

The Treaty of Ghilajharighat and the Humiliation of the Ahoms

The terms were deeply humiliating for the Ahom kingdom. Jayadhvaj Singha agreed to pay a heavy indemnity, surrender elephants annually, provide hostages from leading noble families, and cede territories in Kamrup and Darrang. Most degrading of all, he was compelled to send his six-year-old daughter Ramani Gabhoru to the Mughal court. On 4 January 1663, even before the treaty was formally concluded, the child was dispatched with gold, silver, elephants, and hostages. Mughal records later state that she was forcibly converted to Islam, renamed Rahmat Banu, and married to Prince Muhammad Azam, with her marriage settlement fixed at 180,000 rupees on 3rd May, 1668. This act symbolised not merely political submission but the violent humiliation of Ahom sovereignty and royal dignity.

Retreat from Assam and the Death of Mir Jumla

Mir Jumla ordered the retreat from Assam on 9 January 1663, to the immense relief of his exhausted army. The withdrawal was harrowing, marked by continued disease and death. After leaving Guwahati on 22 February, Mir Jumla’s health rapidly deteriorated, and he died aboard a barge near Khizrpur on 30 March 1663. According to the French traveller Bernier, Aurangzeb received news of his death with thinly veiled satisfaction.

A Hollow Victory and the Reassertion of Ahom Power

In the end, the invasion proved a hollow victory. The Ahoms never fulfilled the treaty’s key provisions. Territorial cessions remained nominal, indemnities unpaid, and Mughal garrisons failed to take root. Within four years, the Mughals were expelled from Guwahati, and in 1671 their imperial ambitions in Assam were decisively shattered at the Battle of Saraighat under Lachit Barphukan.

Treason and Internal Weakness within the Ahom State

The collapse of Ahom resistance during the invasion was compounded by internal defection and treason, most notably by Baduli Phukan, who deserted the Ahom cause and supplied Mir Jumla with crucial intelligence on defensive arrangements and internal dissensions. His betrayal weakened resistance and deepened panic within the Ahom leadership, illustrating how internal disunity proved as damaging as Mughal arms.

Limits of Empire and the Resilience of Assam

Mir Jumla’s Assam campaign thus exposed the limits of Mughal imperial power. It revealed the brutality of conquest, the extraordinary resilience and sacrifice of the Assamese people, and the futility of imposing empire on a land defended not only by arms, but by geography, climate, and an unyielding spirit of independence.

(About the author : DR Raktim Patar is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. His areas of interest include the history, archaeology, and ethnohistory of Northeast)