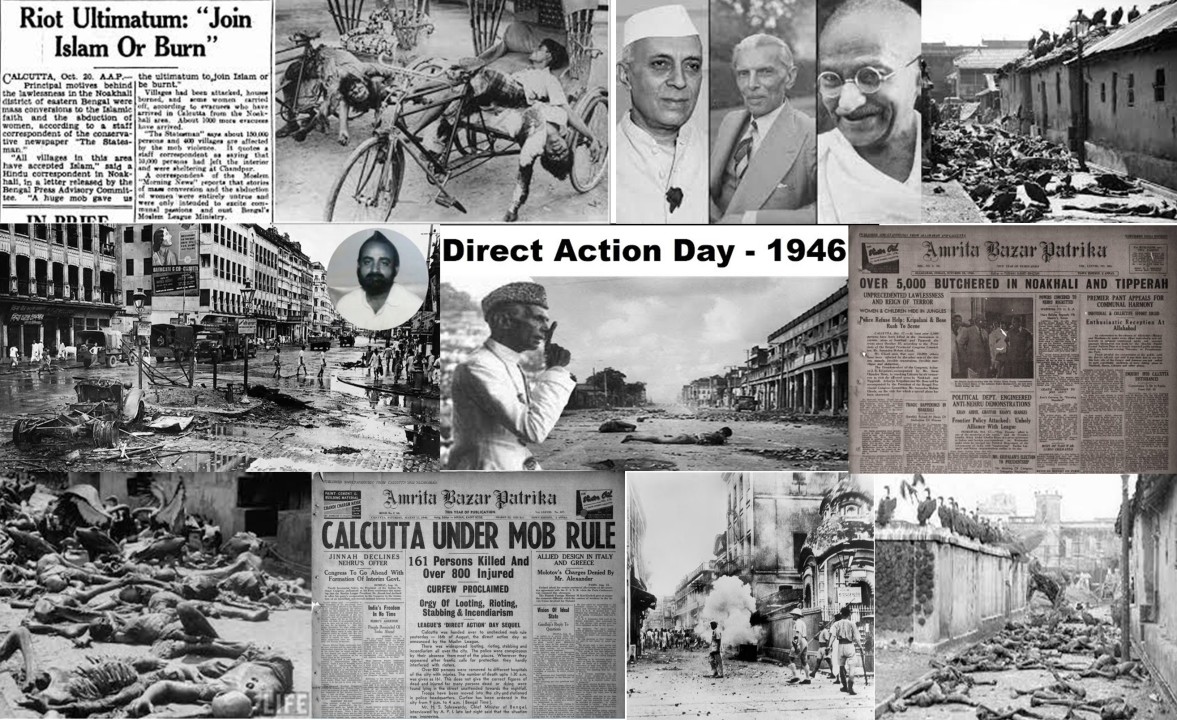

The Great Calcutta Killings and Gandhi’s Miracle of Peace

"From the fiery debates of the Lahore Resolution to the horror of Direct Action Day and the Great Calcutta Killings, and finally Gandhi’s miraculous stand for peace, Bengal’s 1940s became the crucible where Bharat’s freedom was forged and fractured."

Paromita Das

New Delhi, 22nd August: At the dawn of the 1940s, Calcutta stood as a cauldron of political rivalries and communal anxieties, caught between fragile alliances and the rising influence of the Muslim League. Once the jewel of colonial Bengal, the city was fast becoming the stage for some of the most decisive—and devastating—moments in Bharat’s march toward independence and partition. The story of Calcutta in the 1940s is not just about riots and politics; it is about competing visions of Bharat, the cost of communal discord, and the fragile hope of reconciliation offered by Mahatma Gandhi.

The Lahore Resolution: A Turning Point

On March 23, 1940, A.K. Fazlul Huq, the “Lion of Bengal,” presented the Lahore Resolution at the Muslim League’s annual session. Welcomed by Jinnah as “the tiger” whose presence demanded respect, Huq’s proposal sought sovereign states in Muslim-majority regions of British India. Though couched in ambiguity, it later came to be seen as the blueprint for Pakistan.

This resolution did not emerge in isolation. It reflected Bengal’s shifting political tides—where communal identity was being sharpened against the backdrop of British rule, agrarian discontent, and competing nationalist visions.

The Huq-Syama Experiment and Its Collapse

By December 1941, Huq formed the Progressive Coalition government in Bengal, intriguingly partnering with the Hindu Mahasabha. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the Mahasabha leader, became Finance Minister. This odd alliance sought stability but soon fractured under the weight of contradiction.

When the Quit India Movement erupted in 1942, Mookerjee famously urged cooperation with the British, emphasizing order and defense rather than rebellion. The coalition enforced the Defence of Bharat Rules and resisted Congress’s mass protests. But this balancing act collapsed, leaving the Muslim League to dominate Bengal politics by mid-decade.

Direct Action Day: Calcutta in Flames

On August 16, 1946, the Muslim League called for Direct Action to demand Pakistan after talks with Congress and the British stalled. What was intended as a show of strength spiraled into one of the darkest episodes in Bharat’s pre-independence history.

Calcutta, already tense, became the flashpoint. League Chief Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy declared a public holiday, a move widely criticized as dangerous given the charged atmosphere. Massive rallies soon devolved into street battles, arson, and slaughter.

Eyewitnesses, including HV Hodson, described mobs armed with bamboo sticks, iron rods, and knives tearing through neighborhoods. In three days, between 4,000 and 10,000 people were killed, while tens of thousands were maimed. Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs all became perpetrators and victims, the violence feeding on itself with unimaginable ferocity.

The Great Calcutta Killings shattered any illusions of communal harmony. It was a grim preview of the carnage that Partition would unleash a year later.

Aftermath and Escalation

The killings in Calcutta triggered a chain reaction of communal reprisals. In Noakhali, East Bengal, Hindu villages were ravaged, thousands killed, and many displaced. Gandhi walked into this inferno in November 1946, spending months in villages, preaching reconciliation.

But even Gandhi’s presence seemed like a drop in the ocean against the tides of mistrust, violence, and political ambition. As 1947 approached, Calcutta teetered once again on the edge of disaster.

The Miracle of Calcutta: Gandhi’s Last Stand

In August 1947, while the nation celebrated independence, Calcutta braced for fresh riots. Gandhi arrived on August 9 and chose to stay in Beliaghata, a Muslim-majority slum surrounded by Hindu neighborhoods. His decision to live amid the most vulnerable was a deliberate act of moral defiance.

He was joined by Suhrawardy, the very man accused of enabling the 1946 violence. Crowds jeered, hurled stones, and demanded Gandhi’s departure. His response was characteristically disarming: “I have come to serve Hindus and Muslims alike. I place myself under your protection.”

Through daily prayer meetings, appeals for peace, and his sheer presence, Gandhi turned a tinderbox into a fragile sanctuary. On August 15, 1947, while Delhi rejoiced, Calcutta fell silent. Hindus and Muslims prayed together, shared meals, and declared peace. The press called it the “Miracle of Calcutta.”

The Fast Unto Death

Peace, however, remained precarious. On September 1, 1947, renewed violence forced Gandhi into his most dramatic protest: a fast unto death. For 73 hours, he consumed nothing but lime water. As his frail body weakened, rioters surrendered their arms—knives, guns, bombs—at his feet. Leaders across communities pledged peace. On September 4, Gandhi broke his fast with orange juice offered by Suhrawardy.

Lord Mountbatten would later call Gandhi a “one-man boundary force”, whose moral authority achieved what armies could not.

Lessons from a Burning City

The story of 1940s Calcutta is not just a chronicle of communal riots but a profound lesson on the fragility of democracy and coexistence. Political opportunism, communal polarization, and administrative failures created a perfect storm. Yet, amid the ashes, Gandhi showed that moral courage could succeed where politics and violence failed.

Critics may argue that Gandhi’s peace was temporary, a pause before Partition’s horrors engulfed Punjab and Bengal. But even if fleeting, the Miracle of Calcutta revealed that reconciliation was possible—if only leaders had the will to embrace it.

From Violence to Vigilance

The arc from the Lahore Resolution to the Great Calcutta Killings and finally Gandhi’s fast illustrates the contradictions of Bharat’s freedom struggle: hope entangled with despair, unity shattered by division, and peace achieved through sacrifice.

Calcutta in the 1940s remains a haunting reminder that democracy is not built merely on institutions but on trust, restraint, and moral responsibility. Gandhi’s sacrifice did not erase Partition’s scars, but it offered a glimpse of an Bharat that could have been—an Bharat that chose harmony over hatred.

As Hydari Manzil, now Gandhi Bhavan, preserves his memory, the Miracle of Calcutta stands as a timeless warning and inspiration: violence divides, but even in the darkest hours, peace can still be forged by courage.