Poonam Sharma

For years, fragments of information surfaced sporadically—whistleblower claims, obscure documents, unanswered questions. Each time, they were easy to dismiss in isolation. But when fragments begin aligning into a coherent pattern, dismissal becomes denial. What is now emerging around the Cambodia Life Sciences Academy is not a conspiracy stitched together by rumor, but a troubling mosaic of documented partnerships, leaked images, and structural overlaps that raise profound ethical, constitutional, and geopolitical questions.

This is not a story about speculation. It is a story about location, partners, purpose, and power.

The Image That Changed the Conversation

A few days into the recent Thailand–Cambodia tensions, an image quietly began circulating online. On one side was a list of 28 institutional partners of the Cambodia Life Sciences Academy. On the other was a Chinese internal map identifying a facility labeled “Obedient Stem Cell Bone Marrow Extraction Center.”

The term alone is chilling. But more disturbing than the name was the nature of the partners themselves. These were not private start-ups or independent laboratories seeking low-cost overseas expansion. Every major Chinese entity on the list was state-affiliated, state-funded, or state-controlled.

This was not outsourcing. This was state science, exported.

Category One: Hospitals with Long Shadows

At the top of the partner list sat Xiangya Hospital of Central South University in Changsha—a name deeply entrenched in China’s organ transplant controversies. Alongside it was Xiangya Second Hospital, infamous after the mysterious death of whistleblower resident Dr. Roche, who reportedly fell from a building under unexplained circumstances.

The official collaboration focus? Stem cells and regenerative medicine.

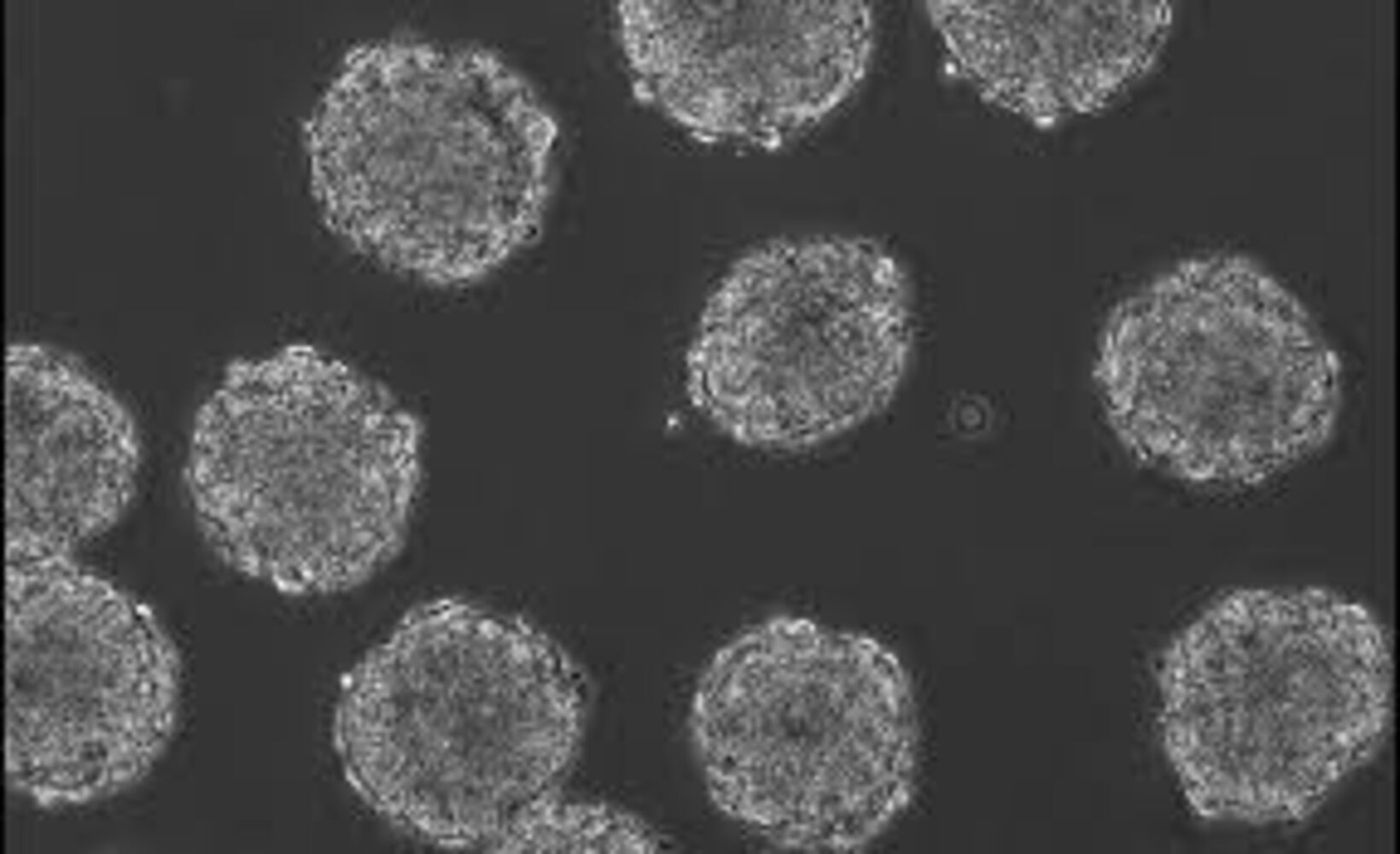

Leaked internal images allegedly taken by staff at the Cambodian institute reinforce this focus. Dated months apart, the photographs show “kidney stem cell” and “liver stem cell” products prepared for male clients, marked with a strict usability window—ideally injected within 90 minutes, viable for only 12 hours.

Such precision implies not experimental theory, but clinical application. And clinical application demands human subjects.

Category Two: Wuhan’s Long Reach

The second category of partners should have stopped the world cold.

Among them was the Wuhan Institute of Virology, operating under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. These are not neutral academic bodies. They sit at the heart of global debates on viral research, biosafety, and state accountability.

Their Cambodian collaboration is vaguely described as “laboratory animal cooperation.” But stripped of bureaucratic language, the pattern points unmistakably toward virus research, infectious disease study, and vaccine-related experimentation.

This raises a fundamental question: Why Cambodia?

Why not Shanghai, Beijing, or Shenzhen—cities with infrastructure, talent, and regulatory legitimacy?

Category Three: Industrializing Biology

Corporate partners such as Beijing Boao Bio and Yuanpingbao reveal another layer. Their projects involve biochip engineering, clinical-grade cell preparation, and cell tissue banks—technologies designed not for isolated research but for scalable, repeatable, industrial biological intervention.

Biochips are not abstract science. They are tools for monitoring, modifying, and controlling biological processes inside the human body. This is the convergence of life sciences and engineering—where experimentation transitions into systems.

And systems require supply.

Category Four: The Soft Front

The final category includes foundations, chambers of commerce, and public welfare organizations—entities that appear benign until viewed in context. Historically, such bodies have often functioned as buffers, creating legitimacy, facilitating logistics, and smoothing regulatory pathways for projects that cannot withstand scrutiny alone.

Seen together, the four categories reveal three unmistakable patterns.

Three Patterns That Cannot Be Ignored

First, extreme officialization. Nearly every Chinese partner is linked to state structures. Even “private” companies trace back to institutions like Tsinghua University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Cambodian facility itself was designed and constructed by an overseas branch of the CAS Architectural Design Institute—a state entity.

This is not rogue science. It is national science.

Second, regional concentration. Over 80 percent of Chinese partners originate from Hunan and Hubei, suggesting a tightly coordinated regional pipeline rather than a global collaboration.

Third, technological focus. Stem cells, gene editing, virus synthesis, vaccines, biochips—these are among the most sensitive and regulated fields in modern science.

Which brings us back to the question that refuses to go away: Why Cambodia?

Scam Compounds and the Supply of Humans

The answer may lie in geography—and governance.

The Cambodia Life Sciences Academy reportedly shares its address with entities linked to the Prince Group, a conglomerate already under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice, with its founder sanctioned by both the United States and the United Kingdom. The group has been repeatedly linked to scam parks and human trafficking networks.

Scam compounds possess one grim advantage no legal research institution can ever replicate: a continuous, controllable supply of human beings—often trafficked, confined, and stripped of legal visibility.

In constitutional democracies, human experimentation is restrained by law, consent, oversight, and ethics. In sealed scam enclaves operating as de facto sovereign zones, those constraints collapse.

According to its own website, the Cambodian institute lists genetic testing, gene editing, and embryonic stem cell preparation and storage among its core businesses. Once biological technology reaches clinical application, it must enter the human body. The only question is under what conditions—and on whom.

A Question the World Cannot Afford to Ignore

Is it plausible that a poor, politically fragile country adjacent to scam compounds could organically attract elite scientists, advanced laboratories, and state-backed Chinese institutions?

Or is Cambodia serving a different purpose altogether—a jurisdictional blind spot where ethics, law, and accountability do not apply?

The evidence does not yet offer courtroom proof. But journalism exists precisely to illuminate patterns before they become catastrophes.

And the pattern here is unmistakable.

When organized crime, human trafficking infrastructure, and state-level biotechnology converge under one roof, the question is no longer whether something is wrong.

The question is how long the world will look away.