Paromita Das

New Delhi, 1st July: In the humid corridors of Kolkata’s jute mills and the green fields of Assam, an old story of fibre and livelihood has found new urgency. After decades of bearing the brunt of cheap jute flooding in from across the border, Bharat has chosen to slam the gates shut—at least partly. The sudden restriction on jute and allied fibre products from Bangladesh marks not just a protective shield for Bharat’s farmers and mill workers, but perhaps the opening act of a sharper, more assertive trade policy toward its eastern neighbor.

What Prompted Bharat’s Latest Ban

On June 27, a seemingly dry notification from Bharat’s Directorate General of Foreign Trade delivered the real punch: Bangladeshi jute would no longer enter Bharat through any land port or seaport—except the sprawling Nhava Sheva port in Mumbai. For a trade corridor that lives and breathes through the border roads of West Bengal and Assam, this was like tightening a belt around Bangladesh’s main arteries.

This wasn’t born overnight. For years, Bharat has watched as Bangladesh’s government poured subsidies into its jute sector. The result? Cheaper sacks, cheaper yarn, cheaper mats—undercutting Bharat’s homegrown industry where millions depend on steady prices to stay afloat. Even previous anti-dumping duties failed to stop the surge. Now, the restriction feels less like a knee-jerk reaction and more like a final boundary being drawn.

Trade Tensions Brewing for Months

To see this decision in isolation would be to miss the larger storm brewing between the two neighbours. Earlier this year, Bangladesh pulled the plug on Bharatiya cotton yarn imports through its land ports, a move Bharat saw as an unfriendly squeeze on its cotton growers. Then came the curbs on rice exports and the long lines of Bharatiya cargo trucks waiting helplessly at border crossings, stuck in layers of checks and paperwork that smelled more of politics than procedure.

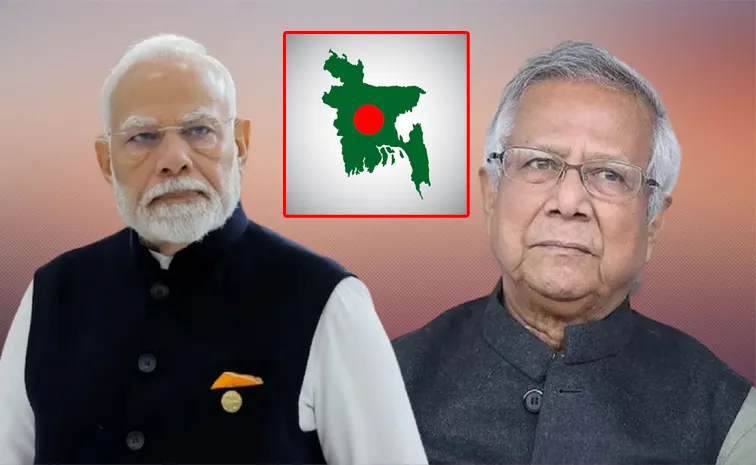

The final straw was perhaps diplomatic, not economic. When Bangladesh’s interim leader Mohammed Yunus stood beside Chinese officials and pitched his country as Beijing’s gateway to Bharat’s northeast, the message in Delhi was loud and clear: Dhaka was flirting with Bharat’s strategic discomfort, throwing open doors for Beijing in a region Bharat guards fiercely.

Winners and Losers in the Fibre War

Behind policy notifications and border checks lie real faces. For Bharat’s jute farmers in West Bengal, Bihar, Assam and Odisha, this ban might feel like overdue justice. For years, they have watched procurement prices slip as cheap Bangladeshi bales took over sacks, ropes, and mats in Bharat’s markets. Mills that once hummed with workers have fallen silent or run at half capacity. The new curb promises to turn the wheel in the other direction—higher prices, better capacity, fewer idle looms.

But trade wars do not come without collateral damage. On the other side of the fence, thousands of small exporters in Bangladesh stand to lose not just money but whole livelihoods. Bharat is not just another customer for Bangladesh’s jute sector; it is the biggest, easiest to reach, and the most lucrative thanks to the shared land border. Blocking that route turns the business of jute into an expensive gamble for Bangladeshi traders. While they can still push shipments through Mumbai, the extra cost and time will sting, and some small players may simply bow out.

A Matter of Principle or Politics?

Many will see Bharat’s restriction as overdue. But is it only about fair trade? The timing hints at something deeper. Bangladesh’s calculated pivot toward China is not lost on Bharat’s foreign policy minds. When Dhaka starts speaking of itself as a ‘guardian of the ocean’ and a ‘gateway’ for China into Bharat’s northeast, it rattles Bharat’s strategic walls.

In that sense, the jute ban is not just about farmers and fibre. It is about showing Dhaka that trade goodwill must align with diplomatic clarity. If Bangladesh wishes to enjoy open access to Bharat’s massive market, it must also respect the boundaries of regional influence.

Turning Trade into a Bargaining Chip

Trade is rarely just about buying and selling. It is about power, leverage, and sometimes, subtle warnings dressed as policy. Bharat’s jute ban tells Bangladesh—and perhaps others in the neighbourhood—that a bigger market means bigger responsibilities. It is also a quiet reminder that subsidies, dumping, and backdoor deals with rival powers may not go unchecked forever.

One might argue that the ban risks fuelling more tensions. But for Bharat, letting local industries bleed while foreign competitors bend the rules is a greater risk. The real test will be whether Bharat can stay consistent—using its market not as a silent recipient of cheap imports, but as a bargaining chip to demand fairer, more balanced trade.

Drawing New Lines in the Sand

Bharat’s decision to choke jute imports from Bangladesh is about more than fibre. It is a small but firm line in the sand—a reminder that neighbourly ties must balance profit with fairness, trade with trust. For Bharat’s farmers and mill workers, this move might just be the breather they have waited for. For Bangladesh, it is a nudge to rethink how far subsidies and strategic drift can stretch before old friends start pushing back.

In South Asia’s tangled politics, the smallest threads can tie up the biggest conversations. And right now, every sack of jute that stays on Bharatiya soil tells its own story about what Bharat is willing to protect—and how.