Bengal’s Vanishing Markets

How the Election Commission's SIR Drive Sparked Panic Across Border Districts

Poonam Sharma

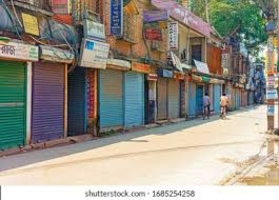

The picture says it all-an empty road where once stood one of the busiest border markets of West Bengal. Stalls shuttered, carts abandoned and silence echoing through lanes that were once alive with traders, buyers and daily bustle. For years, this market near the Indo-Bangladesh border had seen crowds of thousands and business worth lakhs each day. But ever since the Election Commission announced the Systematic Investigation and Review, or SIR, of the voter list, the scene has turned ghostly.

Locals whisper that the traders have “vanished.” Shops are sealed, houses abandoned, and even neighboring villages seem half-empty. Those who stayed behind speak in hushed tones — of fear and uncertainty, of sudden disappearances. “One day they were here, the next day gone,” said a tea stall owner, gazing at the empty street. “They didn’t even take their belongings.”

What is SIR and Why It Sparked Panic

The Election Commission’s SIR operation is meant to “clean” the voter list-verifying identities, removing duplicates, and ensuring only legitimate citizens remain registered. On paper, it is a routine audit aimed at strengthening democracy. But in politically charged Bengal, where the voter list itself has long been a battlefield, the announcement of SIR has unleashed waves of anxiety.

Opposition parties, particularly the Trinamool Congress led by Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, have termed the move politically motivated. The argument is that under the guise of verification, thousands of legitimate voters—especially minorities and border residents—might be struck off. But the reality on the ground reveals another layer: fear among those who may not have authentic documents, and whose voter identity is now under scrutiny.

A Silent Exodus

From Malda to North 24 Parganas, this border belt has reported an unnatural emptiness in its market towns and rural hamlets. Locals maintain that the exodus started within days of the SIR announcement. The mass movement was quiet, almost invisible — no protests, no slogans, just locked doors and uncollected goods.

No official numbers have been given as yet by the authorities, but local traders estimate that hundreds of small shopkeepers, daily wage earners, and even some families have left overnight. Some are believed to have crossed over into Bangladesh; others have simply disappeared deeper into the interiors of Bengal, hoping to avoid verification drives.

A local BJP worker described it more candidly: “When you clean the system, the dirt runs away. Those who have something to hide will always fear transparency.”

Mamata’s Dilemma

The crisis is a serious political and administrative challenge for Ms. Banerjee. While her party has accused the Election Commission of acting under pressure from the center, the disappearance of whole communities from market towns raises uncomfortable questions about illegal infiltration and voter fraud — issues in which the BJP accuses her government of being complicit.

The TMC fears that a large-scale deletion under the SIR process may directly impact its traditional support base. For the BJP, however, this drive could turn into a major political weapon — proof, they claim, that “illegal voters” had been shielding the ruling party.

The Fear of the Unknown

Even genuine citizens avoid appearing for verification in some areas. “People are afraid of losing their ID,” said a school teacher in Cooch Behar. “They think once their name is deleted, they will be branded as foreigners.” The fear runs so deep that even daily market activity has collapsed.

A local observer likened the panic to “acid poured on the skin.” The very utterance of SIR appears to burn through the nerves of these border districts — a metaphorical cleansing that no one saw coming.

Beyond Bureaucracy: The Political Earthquake

If Bengal’s markets and villages are indeed emptying out due to SIR, it is more than just a bureaucratic exercise; rather, it is a social earthquake. It exposes how deep the question of citizenship and identity runs in Bengal’s politics, which has lived for decades with porous borders, waves of migration, and competing political narratives of inclusion and exclusion. Today, that fragile balance appears to have snapped. To some, SIR is long-coming justice-a step to restore the sanctity of Indian democracy. To others, it’s a frightening reminder of how easily livelihoods and identities can be erased at the stroke of a bureaucrat’s pen. As silence descends over Bengal’s border markets, one thing is clear: SIR has not only cleaned up the voter lists, it has exposed the fault lines of a state torn between legality and loyalty. Whether this cleansing process will strengthen democracy or deepen divisions is a question Bengal will have to answer in the days ahead.