By Rakesh Koul

Social Activist & Senior Journalist

For thirty-six long years, the Kashmiri Pandit community has lived as migrants within the borders of their own country. They are a people displaced, often unheard, and eternally waiting for a justice that has consistently remained out of reach. While governments in New Delhi and Jammu & Kashmir have changed hands, and policies have been drafted and redrafted, the ground reality for those forced to flee their homes in 1990 remains tragically stagnant: there is no accountability, no closure, and no true sense of belonging.

The question of what has truly been done over these nearly four decades is often met with a heavy, institutional silence.

A Silent Sentinel for Justice

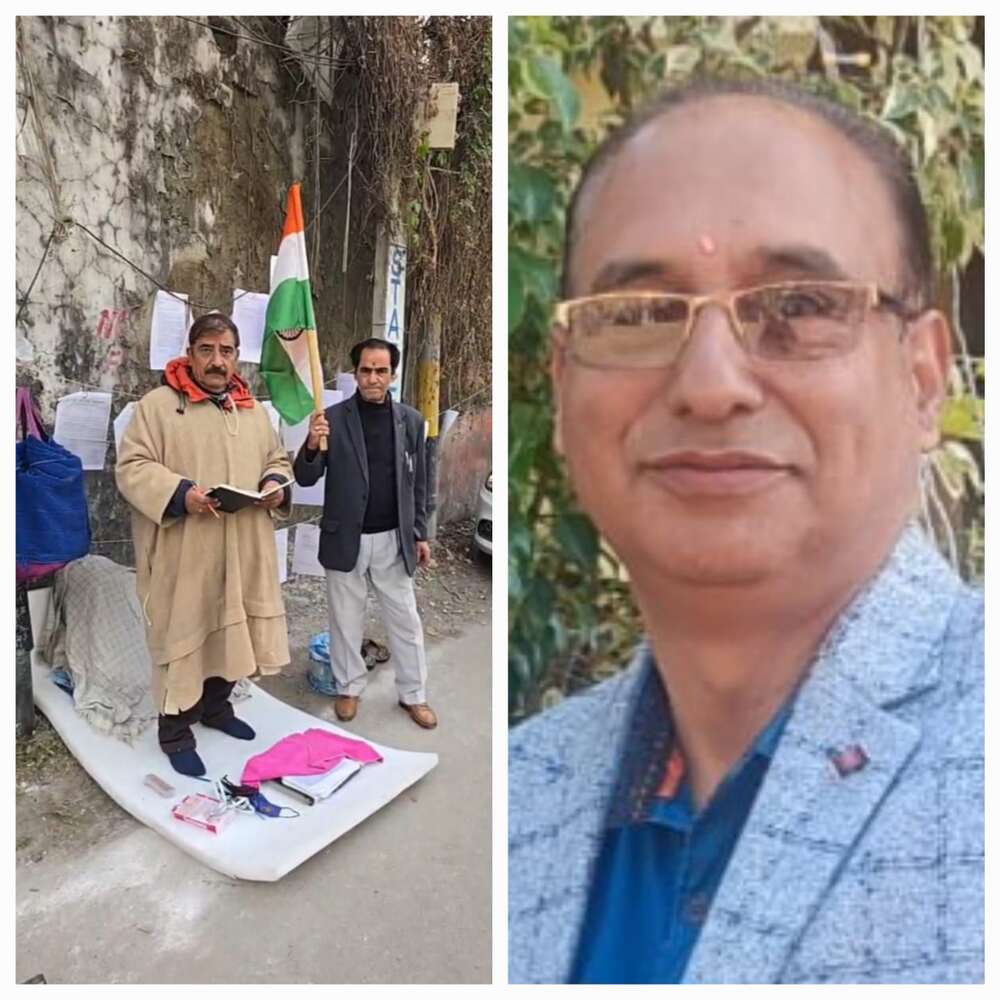

On December 6, 2025, at 11:00 AM, this silence was broken by a quiet but powerful act of defiance. Shri Avtar Krishan Koul, son of the late Shri Shamboo Nath Koul, took a seat outside the Office of the Relief and Rehabilitation Commissioner (Migrants) on Canal Road, Jammu. His peaceful protest, occurring as the community enters its 37th year of exile, serves as a poignant reminder of thousands of similar, untold stories of loss.

Shri Koul did not come with slogans or political banners. Instead, he sat at the gate holding the symbols of his conviction: official documents representing his struggle, the Indian Tricolour representing his faith in the nation, the Bhagavad Gita for spiritual strength, and a lit Diya—a flicker of hope in a long night of neglect. His protest is not driven by partisan politics, but by the raw endurance of a man who has run out of options but has not run out of resolve.

The Anatomy of Neglect

Shri Koul is protesting the systemic failure of successive governments and the Relief and Rehabilitation authorities to ensure the dignity, security, and rehabilitation of the displaced population. His personal grievances are a microcosm of the larger community’s trauma.

One of the most glaring injustices he highlights is the fate of his ancestral home in Tehsil Shahabad Bala, District Anantnag. On December 6, 1992, while the nation was gripped by other turmoils, his house was burned and demolished. In the decades since, there has been no formal investigation, no punishment for the perpetrators, and not a single rupee offered in compensation. It is as if the event—and the home itself—never existed in the eyes of the law.

Barriers Beyond the Physical

The institutional apathy Shri Koul has faced is perhaps more soul-crushing than the physical loss of property. When he formally reached out to the Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) in Anantnag to seek justice for the destruction of his home, he was met with a bureaucratic wall. Instead of a promise of investigation, he was reportedly told that his complaint, written in Hindi, could not be processed. He was instructed to resubmit his plea only in English or Urdu.

This brings us to a fundamental, disturbing question: In a democratic republic, is language now a barrier to justice for a primary citizen? If a victim cannot cry out for help in a language recognized by the Constitution, where does the “rule of law” truly stand?

A Failure of Institutions

Shri Koul’s journey for justice has taken him to the highest echelons of the Indian state, only to be met with jurisdictional deadlocks. When he approached the Supreme Court of India seeking intervention against the atrocities faced by migrants, the response was a reflection of the legal complexities of the era: due to the existence of Article 370 at that time, the Court’s ability to interfere in certain state matters was limited.

This left a displaced citizen in a legal vacuum. If the highest court in the land could not intervene, and the local police refused to accept his language, where was he expected to go? Similarly, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), tasked with being the watchdog of the vulnerable, has yet to provide a decisive resolution to the gross violations of human rights cited by the migrant community.

The Cost of 36 Years

As we look back at the timeline of this displacement, the data remains obscured by a lack of political will.

How many homes were actually razed to the ground?

How many thousands of files are currently gathering dust in government cabinets?

How many families have perished in “temporary” camps, waiting for a return that never materialized?

The promises made to Kashmiri Pandits—return, rehabilitation, security, and compensation—have been replaced by symbolic “packages” and endless assurances. While temporary relief measures exist, they are merely bandages on a wound that requires deep, restorative surgery.

A Mirror to the Nation

Shri Avtar Krishan Koul’s lone protest is not an isolated incident; it is a mirror. It reflects the collective failure of our governance, our legal institutions, and our national conscience. When a citizen is compelled to sit on a sidewalk in the twilight of his life, clutching documents just to be heard by a mid-level bureaucrat, the failure does not lie with him. It lies with a system that has grown comfortable with the status quo of displacement.

The nation must listen to the quiet man with the Diya. Justice delayed for thirty-six years is not just justice delayed—it is a daily, compounding denial of the right to exist with dignity.

The authorities must finally provide answers. The time for “symbolic gestures” has passed; the time for accountability is decades overdue.