Vande Mataram Returns to the Frontline: Parliament Rekindles a Century-Old Rift

“Vande Mataram Debate Returns: A Century-Old Question on National Identity Reignites in Parliament.”

Paromita Das

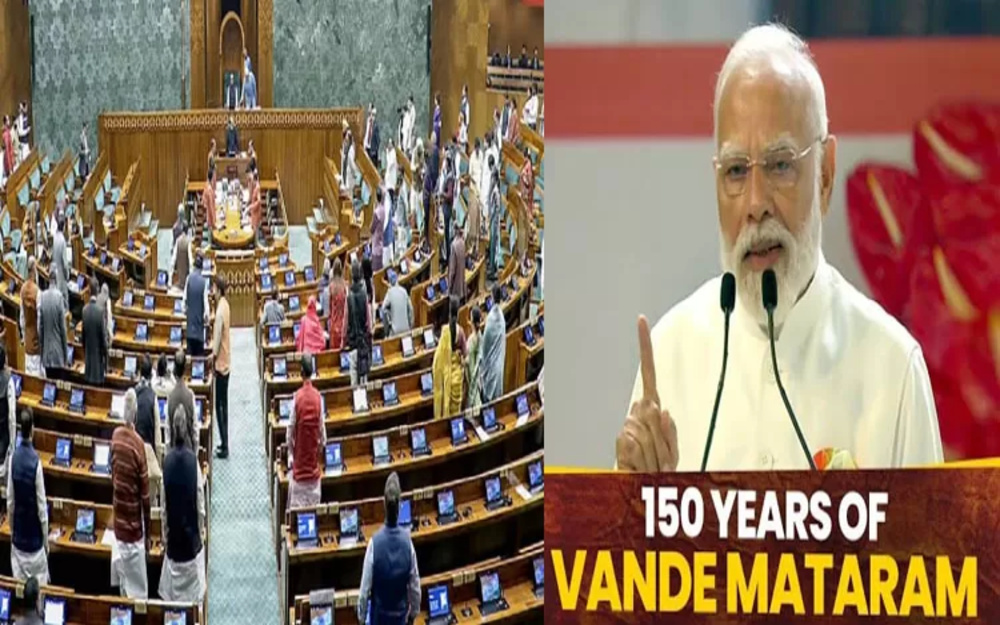

New Delhi, 12th December: In The uproar in Parliament over Vande Mataram has once again reminded Bharat that some debates never truly fade; they only reappear in new political climates. What began recently as an exchange of accusations—Prime Minister Narendra Modi alleging that the Congress “fractured” the national song under pressure from the Muslim League, and the Opposition countering with loud protests—has quickly grown into something far deeper. At stake is not just a song, but a larger conversation about who defines Bharat’s national identity and how far the nation must go in accommodating religious sensitivities.

To an uninformed observer, the disagreement may look like an argument over symbolism or semantics. But to anyone familiar with Bharat’s political history, the tension surrounding Vande Mataram reaches into the ideological heart of the nation. The controversy has resurfaced exactly 150 years after Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay composed the song—almost as if history itself wanted to test whether Bharat has outgrown the anxieties that once divided it.

Where the Resistance Began—and Why It Mattered

To understand the present debate, it is impossible to ignore its origins. In the 1930s, Vande Mataram had already become an anthem of the freedom movement, sung in mass protests, student gatherings, and Congress sessions. Yet, the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah rejected the song entirely. The League argued that bowing to the Motherland was equivalent to idolatry, and that the description of Muslim rulers in Bankim’s Anandamath carried implicit hostility.

Whether these objections were sincere or strategic is still debated by historians. What is clear, however, is that Jinnah used the issue as political ammunition. He weaponised symbolism, framing Vande Mataram as a cultural imposition by the Congress, thereby deepening communal divisions. In 1937, the Congress Working Committee decided to retain only the first two stanzas at official functions—an attempt to placate the concerns, but also a move that validated the Muslim League’s belief that religious objections could influence national practice.

This decision, often overlooked today, had long-term consequences. It taught separatist forces that cultural vetoes could shape political outcomes. In many ways, the logic that led to partition was visible in this early dispute: once national symbols were made negotiable, national unity became vulnerable.

How Bharat’s Leaders Interpreted the Battle Over a Song

Bharat’s intellectual giants of the time did not interpret the controversy uniformly. Sri Aurobindo passionately defended Vande Mataram, insisting it represented devotion to the Motherland—not a religious offering. He warned that surrendering national symbols to religious pressure would fracture the unity necessary for nation-building.

Gandhi, however, tried to find a pragmatic balance. While acknowledging the song’s emotional power, he advised restraint when objections arose, hoping to prevent communal escalation in a politically fragile era.

Ambedkar, interestingly, distanced himself from the idea of romanticising the nation through maternal imagery. His critique was rooted not in religious objections but in the realities of caste divisions, which he believed complicated any singular vision of the nation.

Rabindranath Tagore, meanwhile, took a nuanced approach. He appreciated the first two stanzas for their poetic tenderness but warned that the broader text, especially when tied to Anandamath, could fuel misinterpretation. For him, the truncated version had already become a symbol in its own right—and could serve national unity without unnecessary friction.

Together, these perspectives show that the debate was never simplistic. It was a reflection of Bharat’s struggle to reconcile its cultural heritage with its pluralistic aspirations.

Why the Debate Feels Strikingly Familiar Today

Fast forward to 2025, and the arguments echo almost exactly as they did a century ago. The insistence that Vande Mataram conflicts with religious sentiments mirrors the old logic advanced by separatist leaders before independence. The modern version of this argument—advanced by certain Opposition voices—demands that national symbols be moderated or curtailed if any religious interpretation finds them objectionable.

This worldview is built on the same intellectual foundation as the two-nation theory: the belief that communities must remain culturally insulated, and that national identity cannot transcend religious boundaries unless the majority relinquishes space.

Today, the same reasoning fuels opposition to reforms like the Uniform Civil Code and shapes polarising political strategies such as selective “hate speech” legislation. What appears to be a debate about a song is, in reality, a clash over whether national symbols should carry greater weight than sectarian concerns.

Not About Lyrics—But About the Soul of a Nation

The current protests do not revolve around the literary content of Anandamath, nor are they rooted in genuine discomfort with the poem’s imagery. The resistance has evolved into a broader ideological stance: a belief that national unity must always be filtered through religious sensitivities.

But in a nation as diverse as Bharat, this approach is unsustainable. It forces public symbols into permanent negotiation, always vulnerable to reinterpretation through narrow perspectives. The question then becomes: can a nation truly develop a shared identity if its foundational symbols remain perpetually contested?

The Debate Tests Bharat’s Confidence in Its Own Identity

Vande Mataram is no longer just a song; it has become a barometer of Bharat’s cultural confidence. Those opposing it today are not critiquing poetry—they are challenging the legitimacy of civilisational nationalism. The majority’s willingness to dilute its own cultural expressions for fear of religious backlash has long been interpreted as a sign of hesitation in asserting Bharat’s civilisational roots.

This debate tests whether Bharat sees itself as a civilisation-state capable of uniting its diversity, or a federation of competing religious identities constantly negotiating cultural boundaries.

A Song That Still Defines the National Question

The Parliament may eventually move past this debate, but the ideological struggle beneath it will remain. Vande Mataram continues to expose Bharat’s unresolved tension between pluralism and shared identity. The dispute is not about stanzas or symbolism—it is about whether Bharat allows religious vetoes to define its nationhood.

If history has taught us anything, it is that the moment a country begins surrendering its national symbols, its unity becomes negotiable. And in that sense, the controversy over Vande Mataram remains a test—not of nationalism, but of national confidence.