Why Were the Stanzas of ‘Vande Mataram’ Silenced?

As India celebrates 150 years of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s hymn, Congress faces old questions about its decision to omit four stanzas that embodied the nation’s spirit.

A century and a half ago, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee wrote words that would ignite India’s soul — Vande Mataram. The hymn, published in Anandmath in 1882, became a cry of courage during the struggle for freedom. Its verses weren’t just poetry; they were prayer, reverence, and resistance woven together.

But what happens when a song born from devotion becomes a victim of division?

In 1937, at the Faizpur session, the Congress decided that only the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram would be sung at national gatherings. The reason? The remaining stanzas mentioned Hindu goddesses — Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati — and some within the party felt this could offend Muslim sentiments.

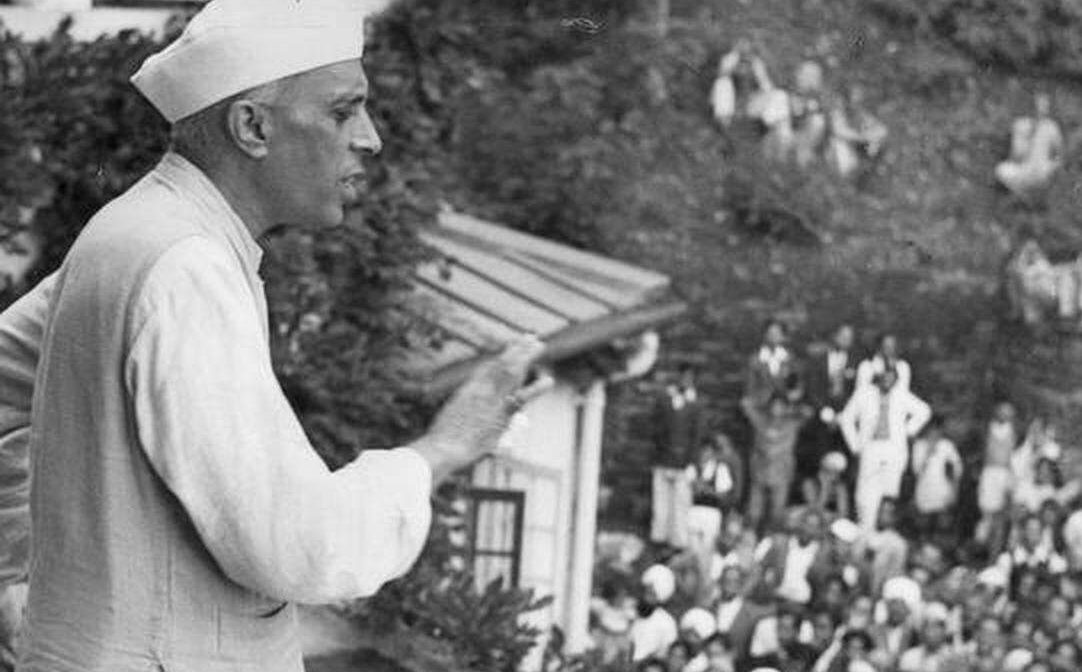

That decision, made under Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership, may have been politically convenient, but was it morally justified?

In those later stanzas lay the essence of the hymn — the image of the motherland as both fierce and tender, divine yet real. Chatterjee’s intent was never sectarian; his verses elevated India to the status of the sacred feminine, symbolising power, purity, and wisdom. By omitting those lines, did Congress reduce Vande Mataram from a hymn of liberation to a sanitized song of political caution?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recitation of the complete hymn on its 150th anniversary was not just symbolic — it reignited a question that Congress has long avoided: why edit a song that united millions during the freedom struggle?

The Congress defends its move as an act of sensitivity, an attempt to protect harmony. But inclusion should never come at the cost of identity. The party that once led the charge for independence must ask itself whether it mistook appeasement for unity.

Nehru’s own letters to Subhas Chandra Bose in 1937 acknowledged the issue’s complexity — he called the interpretation of the verses as “absurd,” yet admitted that “some substance” existed in the communal unease. Still, instead of defending the poem’s cultural integrity, Congress chose to yield.

Eighty-eight years later, that single compromise continues to haunt its politics. Every time Vande Mataram resurfaces, so does the memory of a decision that divided devotion from nationalism.

The truth is, Vande Mataram transcends religion. It celebrates the land, the people, and the spirit of sacrifice. The goddess imagery is metaphor, not theology — the motherland’s strength mirrored in the divine feminine.

So the question remains — did the Congress, in trying not to offend, end up diminishing a symbol that inspired millions to fight for India’s freedom? And in doing so, did it alienate the very emotion that once bound the nation together?

As India sings Vande Mataram 150 years after it was written, it’s time for introspection. Not for the BJP, not for the RSS — but for the Congress, which must ask itself whether it still understands the heartbeat of the song it once shortened.