Vande Mataram: Sliced by Politics, Stolen by Division

“From Devotion to Division: The Untold Story Behind "Vande Mataram" and Nehru’s Silence.”

Paromita Das

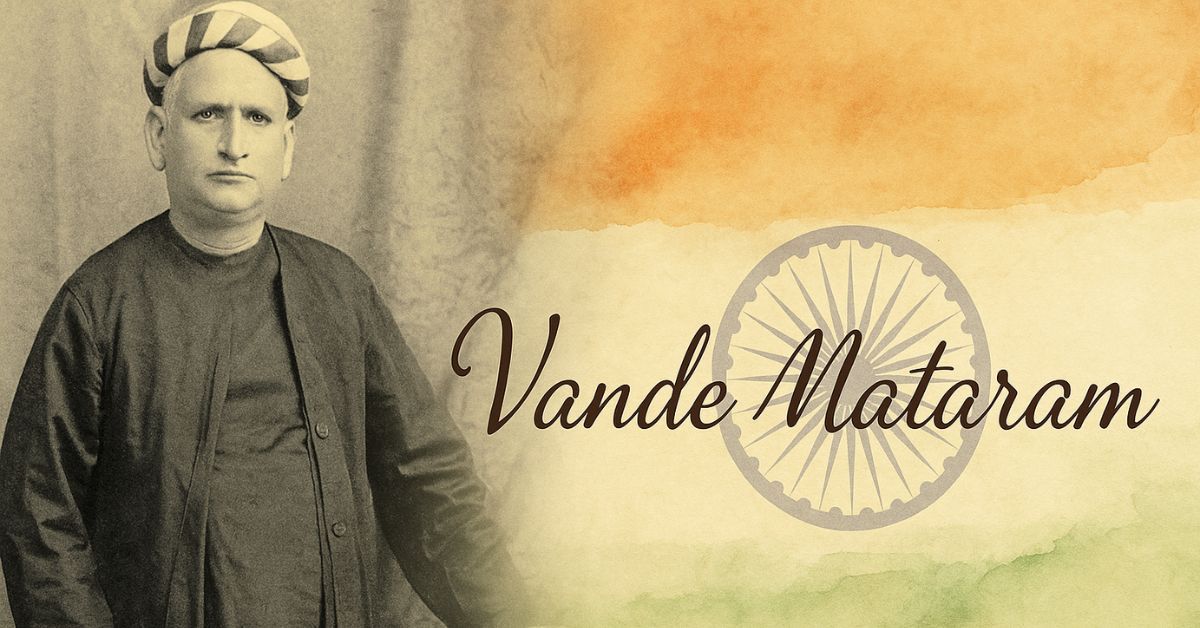

New Delhi, 7th November: On November 7, 2025, the lyric that has resounded in the corridors of Bharat’s political and emotional memory — Vande Mataram — completed a remarkable 150 years since its creation. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Sanskrit-tinged Bengali poem, first written in 1875, grew into the rallying anthem of an emergent republic, later transforming into a site of cultural conversation, contest, and compromise. Now, the government has declared a nationwide celebration: from classrooms to railway platforms, the full version of Vande Mataram will be sung by millions, stamping the song’s enduring symbolic status yet again.

“Vande Mataram” — two words that once ignited the spirit of a sleeping nation — are today recited with reverence at every public gathering. Yet, few know that the same song faced the scissors of political compromise long before the nation achieved freedom. Prime Minister Modi recently emphasized the importance of revisiting the forgotten chapters of this national treasure, reminding citizens how its origins, meanings, and mutilations reveal more about Bharat’s political soul than most history books ever will.

Long before it echoed through the protests of revolutionaries, “Vande Mataram” was poetry — a divine hymn to the motherland. But the journey from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s pen to the lips of freedom fighters, and later to the chambers of the Congress Working Committee, tells a story not of unison, but of appeasement, politics, and identity.

From Poetry to Proclamation: Birth of a National Song

Bankim’s “Vande Mataram” was conceived not as a manifesto, but as a spontaneous celebration of the motherland—woven with motifs of strength, resilience, and devotion. This hymn first found voice in the pages of his novel “Anandamath” (1882), its verses echoing through Bharat’s anti-colonial awakening. Rabindranath Tagore soon gave the poem melody and stature, transforming Bankim’s vision into a living voice of patriotism.

As Dr. R.C. Majumdar has observed, “Vande Mataram sounded the clarion call of freedom, echoing the ancient spirit of mother-worship and patriotism.” The spiritual and cultural roots of the song, tapped through its Sanskrit elements, gave the freedom movement a force that was both modern and timeless.

A Song is Born: Bankim’s Vision of the Motherland

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay wrote “Vande Mataram” in 1875, crafting five lyrical stanzas that blended spirituality and patriotism. Later, in 1882, he included it in his iconic Bengali novel Anandamath, which envisioned Bharat as a divine mother figure — the land and the goddess fused into one.

Rabindranath Tagore lent melody to this creation, giving it a living voice that transcended regions. During the freedom struggle, “Vande Mataram” became a war cry for countless revolutionaries. It was the chant of defiance against colonial rule, the heartbeat of rebellion from Bengal’s lanes to Bombay’s protests.

But as Bharat’s political scene began to fragment, the words that once united started to divide.

The Jinnah Letter: Seeds of Objection and Political Compromise

The year 1908 marked the first storm. The Muslim League declared that “Vande Mataram” had undertones that clashed with Islamic tenets, arguing that its invocation of goddesses like Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati resembled idol worship. The criticism gained momentum, and soon, the debate reached the Congress’ inner circles.

On April 6, 1938, Muhammad Ali Jinnah formally expressed his objection to the song through a letter to Jawaharlal Nehru. In diplomatic language cloaked in political warning, Jinnah demanded that the Congress remove “Vande Mataram” as a national anthem candidate to avoid alienating Muslim representation.

Nehru’s reply was cautious but consequential. He admitted that no song had yet been permanently adopted as Bharat’s national anthem, acknowledging that “Vande Mataram” had indeed become a pillar of Bharatiya nationalism for over thirty years — yet also hinted that some verses might be too controversial for official usage. The Congress Working Committee concurred, deciding to use only the first two stanzas of the song — stripping away the very verses that carried the divine symbolism of the motherland.

Cutting the Soul: How the Original Was Censored

In Bankim’s original version, Vande Mataram celebrated the motherland as both temple and battlefield, where the divine feminine embodied power, knowledge, and prosperity. The removed stanzas described the mother as Durga wielding weapons, as Lakshmi on the lotus, and as Saraswati gifting knowledge.

One such stanza read in translation:

“You are Durga, bearer of ten weapons; you are Lakshmi, pure and graceful; you are Saraswati, dispenser of wisdom. To you, O Mother, we bow.”

It was these lines — rich in Hindu symbology — that were deemed “objectionable.” Thus, the emotional and spiritual intensity that powered the nationalist zeal was politically edited to suit the sensitivities of communal negotiation. The irony remains: the song that unified Bharat against foreign rule became a symbol of internal division.

Politics of Appeasement or Pragmatism?

This act remains debated. Supporters of Nehru’s decision argue that the Congress had to maintain inclusivity in a pre-Partition Bharat torn by communal conflict. Critics, however, see it as the beginning of a dangerous pattern — sacrificing cultural roots to maintain political optics.

Prime Minister Modi’s remarks reignited this debate, asserting that the trimming of Vande Mataram represented “a historical compromise that never needed to happen.” His words echo the sentiment of millions who believe that the spiritual essence of patriotism was diluted for fear of offending a section of the political elite.

The episode exposes a recurring theme in Bharat’s political journey — the balancing act between identity and inclusion, between devotion and diplomacy.

The Cost of Silence

When Nehru accepted Jinnah’s objections, he perhaps believed he was safeguarding national unity. But in trying to prevent division, he inadvertently sowed deeper cultural hesitation. “Vande Mataram” lost part of its poetic body to political surgery — a loss that still reverberates in the nation’s psyche.

Bharat’s freedom struggle was not just a political revolt but a civilizational awakening. By softening the symbols that defined its emotional strength, leaders perhaps underestimated the long-term impact of removing sacred identity from national consciousness.

Reclaiming the Spirit, Not Just the Song

Today, as Bharat revisits its past through debates on heritage and nationalism, “Vande Mataram” stands as more than a melody — it is a mirror. A mirror reflecting how historical decisions, however pragmatic, can reshape a nation’s cultural soul.

Celebrating Vande Mataram’s 150th anniversary is a moment to reflect—not just on how the song mobilized a movement, but on the difficult balancing act between cultural authenticity and political inclusivity. Prime Minister Modi called upon the nation to revisit those forgotten chapters. The government’s mass commemoration has not only revived patriotic fervor but has also reignited debates over identity, inclusion, and the cost of conciliation. Modi’s call to “reclaim the spirit, not just the song” resonates for those who see the original Vande Mataram as integral to Bharat’s civilizational self-respect.

To truly honor “Vande Mataram,” one must remember not just its first two stanzas, but the conviction with which Bankim envisioned Bharat Mata — fierce, enlightened, nurturing. Perhaps, it’s time to reclaim those verses — not for religious assertion, but for historical truth and national self-respect.