Paromita Das

GG News Bureau

New Delhi, 4th June: In the aftermath of the Pahalgam terror attack in May 2025, Bharat’s military retaliation under Operation Sindoor not only neutralized the immediate threat but also sent a message of strategic clarity and decisive governance. As expected, this bold response rattled the Pakistani establishment, both politically and militarily. With its empty threats—most infamously, “Tum hamara paani rokoge, hum tumhara saans rok denge”—Pakistan attempted to portray water as a weapon, not realizing that the geography and hydrology of the subcontinent are not dictated by slogans.

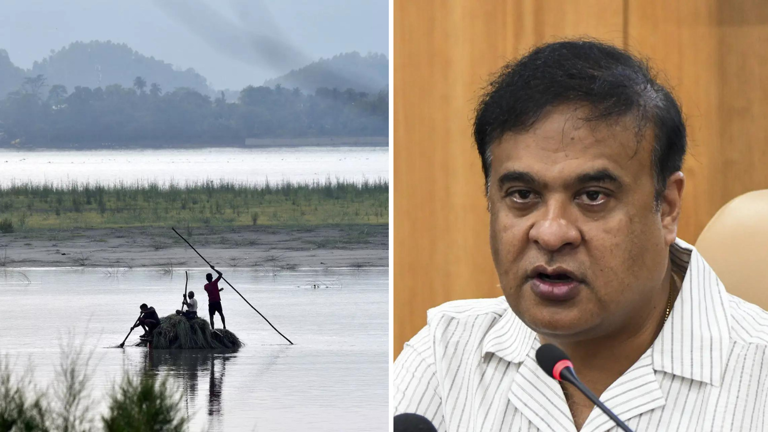

Now, Pakistan has pivoted to another fear-mongering narrative, dragging China into its anxieties by raising the question: “What if China stops Brahmaputra’s water to India?” This manufactured threat, however, has met a factual and composed response from Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, who has comprehensively dismantled this scare tactic with a geography lesson rooted in hard data and hydrological insight.

What If China Stops Brahmaputra Water to India?

A Response to Pakistan’s New Scare NarrativeAfter India decisively moved away from the outdated Indus Waters Treaty, Pakistan is now spinning another manufactured threat:

“What if China stops the Brahmaputra’s water to India?”…— Himanta Biswa Sarma (@himantabiswa) June 2, 2025

Understanding the Brahmaputra’s Flow: The Reality of Rain-fed Power

The Brahmaputra River, known as the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet, flows from China into Bharat and eventually into Bangladesh. While China controls the upper reaches, the majority of the river’s discharge and its real swelling occurs inside Bharat. According to CM Sarma, China contributes only 30-35% of the river’s flow, mainly from glacial melt and high-altitude precipitation. The remaining 65-70% originates within Bharatiya territory—a powerful rebuttal to Pakistan’s speculative threat.

The Bharatiya stretch of the Brahmaputra is fed by torrential monsoon rains, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Nagaland, and Meghalaya. Further hydrological strength comes from a network of tributaries like Subansiri, Lohit, Kameng, Manas, Dhansiri, Jia-Bharali, and Kopili, along with several hill-fed rivers such as Krishnai, Digaru, and Kulsi.

The numbers tell their own story. At Tuting, where the river enters Bharat from China, the flow is estimated at 2,000–3,000 cubic meters per second (m³/s). However, by the time the river reaches the Assam plains, especially around Guwahati, the monsoon inflow swells the discharge to an average of 15,000–20,000 m³/s. This dramatic increase invalidates the idea that Bharat is dependent on China for Brahmaputra’s vitality.

Water as a Weapon: An Unwinnable Battle for Pakistan and China

In trying to rally support or fear via water politics, Pakistan is exposing its strategic weakness. After Bharat suspended the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) following the Pahalgam attack—something long overdue—Pakistan found itself scrambling for leverage. Its attempt to enlist China’s involvement via threats to the Brahmaputra is a reactionary move with little grounding.

Notably, Pakistan is facing its own water crisis. As of May 2025, Pakistan’s Indus River System Authority (IRSA) reported a 21% shortfall in water flow and a 50% live storage shortage at its two main reservoirs—Tarbela and Mangla. This scarcity has directly impacted Pakistan’s ability to grow its kharif crops, especially in agriculturally vital provinces like Punjab and Sindh.

Meanwhile, Bharat is building strategic resilience. In response to China’s upstream hydropower ambitions, New Delhi has fast-tracked an 11,000 MW hydroelectric project in the Upper Subansiri region. This not only improves Bharat’s energy security but also gives it a firmer grip on managing water flow in its northeastern states.

It’s important to highlight that despite Tibet accounting for more than 50% of the Brahmaputra’s basin area, its actual contribution to discharge is limited to 22–30%, due to low rainfall and the high-altitude cold desert environment. This renders Chinese control of the river’s headwaters far less potent than Pakistan claims.

Pakistan’s Manufactured Panic: A Case of Projection

CM Himanta Biswa Sarma aptly called out the Pakistan-China fear campaign for what it is: a geopolitical bluff. His statement, “Brahmaputra is not a river India depends on upstream—it is a rain-fed Indian river system”, reinforces the Bharatiya state’s long-standing hydrological independence.

Even in a worst-case scenario—if China were to reduce water flow—the net effect could be beneficial for Bharat, especially for Assam, where annual flooding displaces over a million people and causes massive economic losses. A marginal drop in upstream flow might actually help regulate downstream flood damage, turning an intended threat into a strategic advantage.

Meanwhile, China has never formally threatened Bharat with water weaponization, despite the potential capability. Any such action could trigger international backlash and complicate China’s image in multilateral forums, particularly as it pushes for leadership in climate and sustainability issues. The statement by Victor Gao, a Chinese think tank official, suggesting Bharat “may face difficulties,” carries no official weight and should be viewed more as rhetorical noise than diplomatic policy.

Geography Favors the Prepared

Pakistan’s attempt to scare Bharat with the China-Brahmaputra card reflects its increasing strategic irrelevance and desperation following decades of exploiting the Indus Waters Treaty without accountability. That era is now over. Bharat has reclaimed its rightful water sovereignty, backed by geography, monsoon-fed rivers, and civilisational resilience.

By invoking manufactured threats rather than addressing its own structural failures, Pakistan is not only undermining regional peace but also eroding its own credibility. Bharat, on the other hand, is responding not with panic, but with preparation—developing infrastructure, leveraging hydrological knowledge, and diplomatically neutralizing false narratives.

The Brahmaputra does not bend to empty threats. It flows—like Bharat’s resolve—independent, strong, and fortified from within.