GG News Bureau

New Delhi, 12th Jan. In the six decades since Partition, Bharat’s population has more than tripled, rising from 36.1 crore in the 1951 census to more than 120 crore in 2011. According to the United Nations Population Division, Bharat gained approximately 1 million people each month in 2020, putting it on track to overtake China as the world’s most populous country by 2030.

Though religious communities developed at varying rates between 1951 and 2011, every major religion in Bharat increased in size. Hindus, for example, jumped from 30.4 crore to 96.6 crore, Muslims from 3.5 crore to 17.2 crore, and Christians increased from 0.8 crore to 2.8 crore.

In the twentieth century, Bharat’s population growth coincided with an economic change that resulted in significant increases in life expectancy, living standards, and food production. Experts agree, however, that the population increase has hampered Bharat’s economic progress by putting stress on schools, health services, and natural resources.

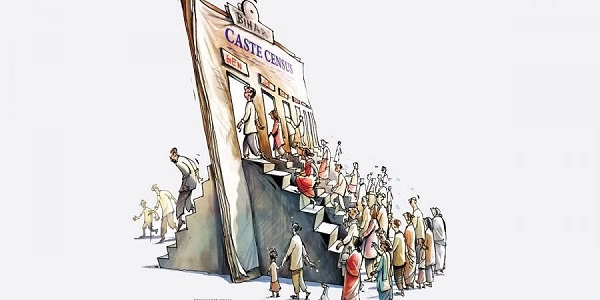

So, why does Bharat need an unbiased census devoid of caste and religion?

For that matter, we have to understand the caste structure and the reservation benefits offered by the Bharatiya government to those belonging to various castes.

Castes are hereditary social classes in Bharat. Historically, the caste into which a person was born influenced their social rank, as well as their available social circle and the vocations they might follow.

Three-quarters of Bharatiya are from a historically disadvantaged group

In order to lessen the disadvantages created by caste, the government maintains affirmative action programmes known as “reservations.” The Bhrartiya constitution reserves 15% of government jobs and places in higher education institutions for those designated as belonging to Scheduled Castes, 7.5% for Scheduled Tribes, and 27% for “Other Backward Classes” (OBCs).

Bharat needs a fair and unbiased census in order to preserve population equilibrium so that every citizen gets the benefits provided by the government.

The Census Act of 1948, which does not prescribe a time frame for the government to complete the exercise or report the findings, governs Bharat’s census. It is an ambitious project that will yield a wealth of vital data for administrators, policymakers, economists, demographers, and anybody else interested in where the world’s second-most populous country due to overtaking China this year is headed. It is used to make judgements on everything from providing federal cash to states to building schools to establishing electoral constituency borders.

When the pandemic struck, Bharat was about to conduct the first round of the census, which collects housing data. While travel and movement were restricted while officials dealt with more serious matters, the exercise was postponed.

Because the government continues to rely on population statistics from the 2011 census to decide who is eligible for help, it is believed that over 100 million individuals are excluded from the Public Distribution System (PDS). The immediate impact of the census delay will be on the PDS, which is how the government distributes food grains and other necessities to the poor.

Population growth in Bharat has slowed, particularly during the 1990s.

Population growth has slowed in part as a result of such policies, notably during the 1990s. After a nearly 25% increase in the 1960s and again in the 1970s, growth in the 2001–2011 census decades fell below 20%.

Since the 1950s, Bharatiya governments have collaborated with international organisations to promote a variety of birth control measures, including contraception and compulsory sterilisation. Today, several states and territories penalise large families by prohibiting parents with more than two children from accessing social benefits or running for political office.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare of Bharat launched a comprehensive family planning programme in 2017 with the goal of reducing fertility to replacement levels by 2025 by improving health care facilities, access to contraception, and reproductive health education, particularly in areas with relatively high fertility rates.

Along with the census, the government recently indicated it would conduct a demographic survey to update the National Demographic Register (NPR). However, critics said that the NPR would be a list from which “doubtful citizens” would be challenged to establish their Indian citizenship. The criticism comes in the wake of a contentious 2019 citizenship bill, which opponents claim targets India’s 200 million-plus Muslims and has triggered months of protests across the country.

Bharat already has the majority of the world’s Hindus. In 2010, Bharat was home to 94% of the world’s Hindus, and this is likely to continue in 2050, when the country is forecast to have 1.3 billion Hindus.

However, Bharat is anticipated to have 311 million Muslims by 2050 (11% of the worldwide total), making it the country with the world’s largest Muslim population.

Muslims are predicted to increase quicker than Hindus due to the fact that they have the youngest median age and the greatest reproductive rates among India’s major religious groups. Indian Muslims had a median age of 22 in 2010, compared to 26 for Hindus and 28 for Christians.

Because of these variables, Bharat’s Muslim population will grow faster than its Hindu population, growing from 14.4% in 2010 to 18.4% in 2050.

Unauthorised immigration is a contentious issue in Bharat

Unauthorised immigration is a contentious issue in Bharat, and it is nearly impossible to track correctly over time, especially as regulations governing legal or protected status have changed over time. While Bharat has been prepared to accept refugees, they are usually not granted legal status and are expected to return to their home countries as soon as circumstances permit. According to some sources, tens of millions of people from Muslim-majority nations are living in India without legal status or identification, but a lack of evidence for equivalent outmigration and other indications has cast doubt on the veracity of such high numbers.

According to available data, Muslims are more likely than Hindus to leave India, while immigrants from Muslim-majority countries are disproportionately Hindu. The migration of Hindus from Bangladesh to India, fuelled by sectarian warfare, is largely responsible for Bangladesh’s Hindu population steadily declining.

The recent enormous exodus of predominantly Muslim Rohingyas from Myanmar has also been identified as a source of illegal migration to Bharat. While it is possible that many Rohingyas are in India, prior to the huge exodus in 2017–2018, just roughly 1 million (10 lakh) Rohingyas lived in Myanmar. Following that, the UN estimated that there were roughly 50,000 Myanmar-born people living in Bharat, including approximately 18,000 Rohingya refugees registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Officials in Bharat estimate that there are 40,000 Rohingyas spread across the country.

The Census of Bharat missed 27.85 million individuals in 2011, a population nearly the size of the state of Punjab at the time. While the rate of omissions is higher in urban Bharat than in rural Bharat, it has marginally improved in urban regions while constantly worsening in rural areas, implying that the Census has missed more and more people in rural areas every decade.

Urban illiterate men and women have the highest emission rates. Other relatives and unrelated people living in the housing unit are more likely to be left out of the census than the immediate head of the household and his or her spouse and children.

The sample surveys will inevitably contain some inaccuracies due to the sampling procedure, and other attempts to register all or most people will leave out some of the most marginalised people. Bharat’s voter list, for example, has a gender bias, with women being excluded in far greater numbers than men. In the most recent Delhi elections, nine lakh more men registered to vote than women.

All of this information speaks to one problematic element of all censuses and official surveys: they omit a lot of individuals, especially those on the outskirts. Hence, the government must alter the parameters for conducting the census so that the rights of genuine citizens are not jeopardised.