By Poonam Sharma

In a pioneering study that has the potential to transform the war against malaria, scientists have found that nitisinone, a medication generally prescribed for rare genetic disorders, can make human blood toxic to mosquitoes. The novel strategy marks a new front in vector control, especially in the continuing struggle against malaria—a disease that continues to kill hundreds of thousands annually, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa.

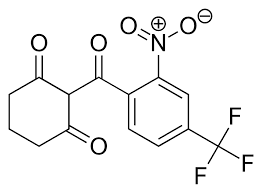

Nitisinone inhibits the action of an enzyme called 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), which plays a key role in the metabolism of some amino acids in human beings and in mosquitoes. Blocking this enzyme disables the mosquito’s capacity to effectively digest blood meals. This triggers the accumulation of toxic metabolites in the mosquito, which ends up killing the mosquito. The significance of this finding is deep, as it provides a new window for managing mosquito populations without the exclusive use of conventional insecticides.

Malaria is still one of the most serious public health issues in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that there were an estimated 241 million cases of malaria in the world in 2020 and 627,000 deaths due to the disease. Anopheles mosquitoes, particularly the female species, are the main vectors of transmitting malaria. Insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual spraying, and environmental management have been the strategies to control these vectors so far. However, the trend is changing as resistance against these insecticides is on the rise, making most methods useless.

The availability of nitisinone as a method to make human blood lethal to mosquitoes may prove to be a valuable addition to existing vector control measures. Significantly, this approach holds promise against many mosquito species that are resistant to traditional insecticides. By attacking the digestive tract of the mosquito and not the nervous system, scientists may have developed a method for evading the resistance to existing insecticides that has dogged them.

The public health impact of this finding is gigantic. If nitisinone is safely provided to vulnerable populations, it will have a twofold advantage: it will cure patients with genetic disorders and, at the same time, decrease malaria transmission. This could be highly desirable in endemic areas where malaria is common and where healthcare service is poor.

Additionally, the application of nitisinone might bring about a paradigm shift in controlling malaria. Rather than killing or biting-avoidance, this approach counters the very process on which mosquitoes depend for survival off human blood. By rendering blood toxic to the vectors, we may significantly curtail their numbers and thus reduce malaria transmission.

While the findings of this study are encouraging, a number of challenges must be overcome before nitisinone can be used as a malaria control method. Foremost among these is the requirement for large-scale clinical trials to test the safety and effectiveness of the drug in diverse populations, especially where malaria is endemic. Scientists will have to ascertain proper dosing and possible side effects, along with long-term consequences of nitisinone use in this new application.

In addition to that, ethical concerns about employing a drug essentially used for curing genetic diseases within a wider initiative for public health have to be examined. Its ability to carry potential unforeseen outcomes, either as ecological influence or impact upon non-targeted species, is also to be rigorously weighed.

As more research is done, scientists are hopeful for the future uses of nitisinone in the control of malaria. The research done by scientists at the University of Notre Dame is only the first step in researching this new method. Future research will probably involve refining dosage regimens and determining how best to combine this method with current malaria control methods.

Coordination among researchers, public health authorities, and policy makers will be essential to get this research from the laboratory into practical applications. If nitisinone is successful, it may be a model for the development of other drugs that attack mosquito vectors in similar manners.

The finding that nitisinone renders human blood lethal to mosquitoes represents a major breakthrough in the battle against malaria. By offering a new means of vector control, this groundbreaking approach promises to lower malaria transmission rates and save thousands of lives. As scientists continue to study its potential uses, there is hope that we are on the verge of a public health breakthrough that will alter the trajectory of malaria eradication efforts for generations to come.

Comments are closed.