By Poonam Sharma

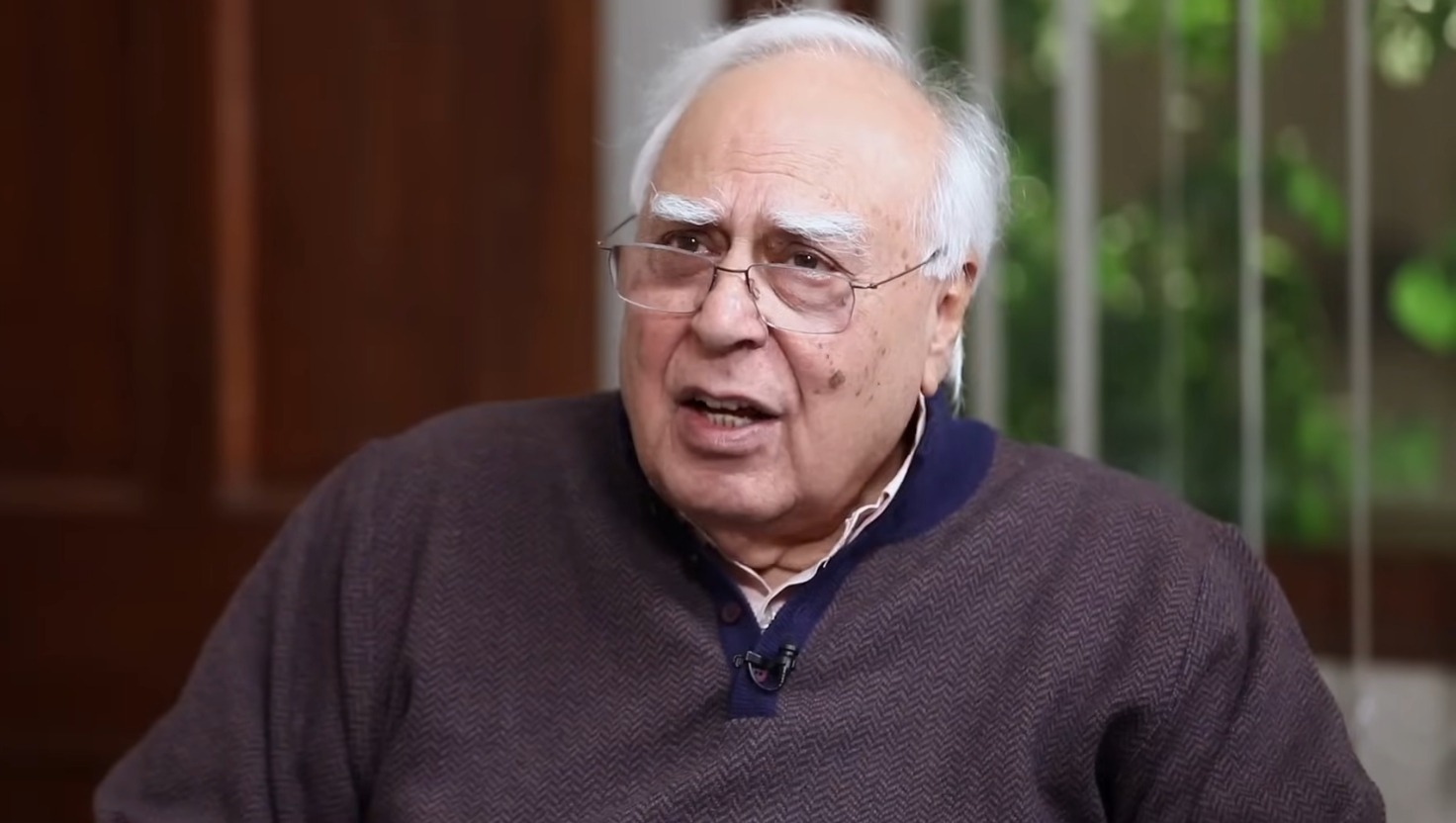

In the wake of the violent protests in Murshidabad and Bhangar, West Bengal—where mobs allegedly linked to radical groups rampaged through streets, torched vehicles, and reportedly targeted Hindus—a striking legal and ethical dilemma has emerged. The man leading the legal charge against the very law these mobs claim to oppose is none other than Kapil Sibal, a Rajya Sabha MP and senior advocate.

Sibal, who was elected to Parliament to make laws, is now standing in the Supreme Court representing Muslim groups like the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, challenging a 2025 amendment that restructured and restricted the powers of religious trusts—including Waqf boards. Ironically, it is this law that protestors on the ground claim has provoked them into violent action.

Which raises a deeply troubling question: Is Kapil Sibal, a Member of Parliament, fighting a legal battle on behalf of those whose supporters are burning public property and attacking Hindu communities in the name of “opposing injustice”?

And more importantly—should he be allowed to do so?

What the Law Says: Does the Advocates Act, 1961 Bar MPs From Practicing Law?

The short answer: No, it doesn’t. But that’s not the whole story.

Under the Advocates Act, 1961, and specifically the rules framed by the Bar Council of India, a person “engaged in full-time salaried employment” is barred from practicing law in Indian courts. This clause is aimed at preventing government employees, company officers, and bureaucrats from moonlighting as lawyers while receiving a salary from another entity.

But MPs don’t fall neatly into that category. They are not “employees” of the government in the traditional sense. They receive a salary, yes—but that does not amount to full-time employment under existing definitions.

This was clarified in multiple precedents, including Ashwini Upadhyay v. Union of India (2018), where the Supreme Court observed that being an MP does not automatically disqualify a person from practicing law.

So, legally speaking, Sibal is in the clear. But here’s the real issue: just because something is legal, does that make it right?

Kapil Sibal is not just fighting a dry constitutional case. He is actively representing petitioners from the very ecosystem that has sparked real-world violence—in this case, the Islamist-leaning organizations whose sympathizers were on the front lines of the Murshidabad rampage.

Let’s be clear: Two Hindus were killed. Police vehicles were torched. Hindu homes and temples were attacked. All under the guise of “protesting” a law passed by Parliament.

And yet, in the Supreme Court, we find a sitting MP—elected to protect constitutional order—arguing in favor of the very groups whose ideological narrative fuels this unrest. Isn’t this a serious breach of public trust?

As a lawmaker, Sibal is supposed to work within the democratic framework. But as a lawyer, he’s helping dismantle it by questioning the legitimacy of Parliament’s legislative authority—and representing those who have chosen street violence over democratic process.

India is not new to the concept of lawyer-politicians. From Motilal Nehru to Arun Jaitley, many have juggled courtrooms and constituencies. But there’s a critical difference.

Arun Jaitley, once he became a Cabinet Minister, voluntarily stopped practicing law. P. Chidambaram, though a senior advocate, also stepped back from legal practice while holding high office.

Sibal, however, seems to believe he can wear both hats indefinitely—MP by day, activist-lawyer by court appearance. The ethical tightrope he’s walking would be laughable if it weren’t so dangerously consequential.The Political Bias Behind Legal Representation follows and

there is also a growing perception that Kapil Sibal only takes up Muslim-centric cases—from Triple Talaq, to Ayodhya, to the Citizenship Amendment Act, and now the Waqf law reforms. Critics argue that Sibal seems more invested in defending Muslim political identity than in representing broader constitutional concerns.

While lawyers are, of course, free to take up any brief, the consistent alignment with one community’s religious leadership—especially while being an active politician—raises red flags. Is this legal representation or selective political patronage under the guise of legal activism?

And when that patronage overlaps with violent street mobilization, the danger isn’t theoretical anymore. It’s real.

Breach of Parliamentary Responsibility

Parliament is where laws are debated and made. MPs have ample opportunity to speak, argue, oppose, and suggest amendments. If Sibal disagreed with the 2025 amendment, he could have used the floor of the Rajya Sabha to express his dissent.

Instead, he chose to bypass the democratic forum and weaponize the judiciary. This sets a dangerous precedent: MPs using their legal license to challenge Parliament itself, not in the spirit of justice, but in service of their political and ideological allies.

One must ask: Whose mandate is Sibal truly representing—his constituents or his clients?

A Disservice to Democracy

At a time when India is grappling with rising communal tensions, judicial backlogs, and increasing distrust in institutions, the last thing the system needs is lawmakers who moonlight as lawyers for mobs. Sibal’s conduct, while not technically illegal, undermines the sanctity of Parliament and the dignity of democratic process.

It tells the public that even the men and women who make our laws don’t fully respect them—and are happy to act as mercenaries in the courtroom if the cause suits their ideology.

Legal, But Not Legitimate

Yes, the Advocates Act, 1961 does not prohibit an MP from practicing law. But lawmakers must hold themselves to a higher standard than merely following the letter of the law. They must lead by example—not just legally, but morally and ethically.

Kapil Sibal’s courtroom crusade against the 2025 law—on behalf of organizations associated with street violence, communal rhetoric, and anti-Hindu aggression—may be legal, but it is not legitimate. It is certainly not just.

And in the long arc of Indian democracy, there is more at stake than just courtroom victories. There is the future of constitutional integrity, communal harmony, and the line that separates democratic dissent from organized disruption.

Kapil Sibal may win his legal case. But in the court of public conscience, he has already lost.

Comments are closed.